From the Archives

Swank in the Arts: John Ardoin profile on Maria Callas

Special | 29m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

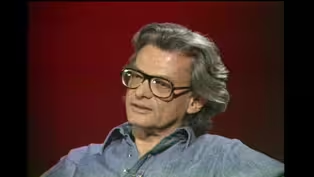

Patsy Swank talks to then-Dallas Morning News music critic John Ardoin for a profile on his friend,

In this episode of Swank in the Arts, broadcast on November 29, 1978, arts reporter Patsy Swank talks to then-Dallas Morning News music critic John Ardoin for a profile on his friend, opera legend Maria Callas.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

From the Archives is a local public television program presented by KERA

From the Archives

Swank in the Arts: John Ardoin profile on Maria Callas

Special | 29m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode of Swank in the Arts, broadcast on November 29, 1978, arts reporter Patsy Swank talks to then-Dallas Morning News music critic John Ardoin for a profile on his friend, opera legend Maria Callas.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch From the Archives

From the Archives is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Take a tour through 65 years of KERA programming.

Swank in the Arts: Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon discusses photography, his inspirations, and The Amon Carter's IN THE AMERICAN WEST. (29m 15s)

Nowhere But Texas 1 nostalgically explores fascinating but seldom-heard Texas stories. (58m 16s)

Legacies of the Land: A Tale of Texas

The show is an armchair tour through the legends, tall tales, and oil wells that pervade Texas land. (59m 25s)

A Conversation with Stanley Marcus

Stanley Marcus discusses how he transformed a small specialty shop into a global retail business. (26m 5s)

A Conversation with Jane Goodall

In 1990, journalist Lee Cullum talked with ethologist and conservation activist Dr. Jane Goodall as (29m 21s)

With Ossie & Ruby: Solo Song for Doc

a 1940s-era drama about Doc Craft, a dining car waiter who realizes his company wants him to retire. (29m 18s)

With Ossie & Ruby: Ghost Stories

The episode, “Ghost Stories,” aired in April 1982, with special guest, respected (30m 15s)

Profile: Lillian Hellman, Episode 4

Lillian Hellman discusses her financial struggles, her partner Dashiell Hammett, and her childhood. (29m 32s)

Profile: Lillian Hellman, Episode 3

Video has Closed Captions

Writer Lillian Hellman discusses the McCarthy era, Watergate, and her perspective on leadership. (29m 5s)

Business Edition with David Johnson: Howard Putnam, Braniff

David Johnson speaks with CEO Howard Putnam, who speaks positively about Braniff's outlook. (28m 46s)

Video has Closed Captions

Helen Hayes invites viewers to celebrate some of America’s greatest treasures - wildflowers! (27m 40s)

Video has Closed Captions

The museum is an architectural achievement of modern times. Hear from its founder and architect. (23m 14s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGood evening.

I'm Patsy swank.

If any one performer can be said to have changed the face of opera in this century, that performer was Maria Callas.

Some singers had greater voices, some equal dramatic gifts, some a presence almost as magical.

But none combine them all for the compelling service to music, as did the New York born Greek girl who grew up to be the legendary Maria Callas.

Her life and career are the subject of a film to be seen Saturday evening at 8 p.m. on KERA and the entire PBS network.

Its producer is Peter Weinberg of New York's Wnet 13.

Its writer is John Ardoin, music editor of The Dallas Morning News and author of two books on Callas.

He was also her longtime friend.

Maria Callas had a close personal relationship in Dallas.

Lawrence Kelly, founder of the Dallas Civic Opera, and Nicola Cino, its artistic director, officiated at her American debut in Chicago in 1954 and were supportive and helpful during her managerial and personal problems at that time.

She never forgot that.

And Callas, it was who presented the benefit concert that was the beginning of the Dallas Civic Opera in 1957.

She came back as Medea, as La traviata, and as Lucia Lammermoor in the following seasons, and she was in Dallas, in fact, at the time of her historic firing from the Metropolitan Opera.

But after 1959 she did not sing opera again in Dallas.

Aristotle Onassis came into her life, and she returned to Dallas only after he had left it.

She took refuge with Kelly and Rational and others of her Dallas friends.

When Onassis engagement to Mrs. Kennedy became known, she promised at that time to return to the Dallas Company, but she never did.

She sang here only once again during the sad and ill advised concert tour of 1974.

Lawrence Kelly died on September 16th of that year in Dallas.

Maria Callas died in Paris two years later, on the same day.

John, where did you first know Maria Callas?

Well, you mean personally?

Yes, because I think I've always known her as an artist.

I can't remember a time when I didn't respond to her, which was, of course, through records first.

But I first met her in Paris in 1964 when I went to, cover performance as she was doing there of Norma at the opera and, it was purely by hook and crook.

I managed to get an interview with her.

She wasn't too happy with journalists at that point in her life.

But I did get an interview, and, I was told I'd have 20 minutes, and we wound up talking for about two hours.

But I think we really became friends.

In the summer of 68, which I'm sure you remember her visit to Dallas at that time.

Very well.

She had been on vacation in Mexico with Larry Kelly, the former the founder of the Dallas Civic Opera.

And, had fallen and cracked a rib or something.

So she came to Dallas to have it looked at.

And, Larry had been with her most of the summer, escorting her around.

That was just before the announcement of Mr. Onassis's forthcoming marriage.

And, I think he was a little glad to get back to his office and out from underneath the pressures of modernism, shall we say.

I sort of fell heir to ride away.

I took her to the doctor and, we went grocery shopping and did all sorts of wonderful, mundane things together.

And, at that point became very, very close.

What there are a lot of other, writers and journalists that have passed through her life, I'm sure, who never managed that.

What was what was it?

Do you think about the two of you that met, that made this friendship so strong and yet so clear?

I don't know, Patsy.

I know that, Maria had this sort of antenna about people.

I took our friendship is a great compliment in that she decided right away that somebody was a good guy or a bad guy.

And really, it was like, almost the way she prepared roles and all it was.

Everything was done with just that basic instinct about about music, about people, about situations.

And, for some reason, she decided I was a good guy and, so much so that she opened up to me in a way that at first, to me was rather almost embarrassing because she was she talked so intimately about things in her life and her feelings and all.

But that was just Maria.

If, you know, she felt instinctively that she could rely on you, our trust you.

Then she opened up as though she had known you for 20 years as such.

And, I think also because she trusted Larry so much.

And Larry and I were good friends, was that constant that anything ever happened to to change it?

Yes, I'm afraid it did.

In that when she made her last concert tour, in 73, 74, you remember in Dallas, as much as I wanted to believe, and as much as I wanted to cheer, I wasn't able to.

To me, it was a very sad occasion because she was fighting very hard to find an identity.

She'd been away from the stage for eight years, and, she wanted to believe.

And this woman, who was usually so fiercely honest about everything and so fiercely self-critical, was for the first time that I had ever known her or anyone else, really sort of deluding herself.

And I think she knew by that point that I wasn't going to lie to her, that I was going to tell her the truth.

And, which I tried to do as gentleman gentlemanly as possible.

And, she didn't want to hear the truth at that point.

And, so it caused a, wrench between us.

Well, you had told the truth about her before your your, reviews had not been uniformly praising.

No.

As a matter of fact, the spring before, when she was at the Juilliard School of Music doing masterclasses, I was taking her one of the eye doctor because she developed glaucoma and, she said to me, out of the blue, she said, Larry tells me you don't like my new record, which was a recording of things she had done many years before, but it suppressed and finally allowed to be issued.

And I said, don't worry, I don't.

And she said, tell me why.

And I told her that I didn't think that they were, that they did her justice and that her first instincts to suppress them had been the best ones.

And she thought about it for a moment.

She said, well, we'll see, but I appreciate your telling me.

But the difference was, I think Patsy at that time, she wasn't under the pressure performing.

She wasn't back in, harness, shall we say, needing to believe in herself, needing to hold on to, our find that identity she had lost.

So she didn't feel threatened so she could accept the truth with more grace.

That's why maybe I was foolish, but that's why I felt I could say the truth when she was here in 74.

But that I misjudged.

I don't really regret it.

I, I would, I would do it again, but I was sorry it led to a breach between us, which, I was unable to repair before her death because I, I had fierce, fierce admiration for the woman and the human being as much as for the artist.

And, if this was a slight fall from grace or a slight, Achilles heel, I think she was entitled to it by that point.

I just wish that I could have believed more with her at the time.

How did you become involved with this film?

Well, about a year ago, there was to be, a convention in Houston by the Central Opera Service.

And, part of the meeting, it was a national meeting was to be a panel on television and opera.

And I was asked to serve on the panel.

And, it's a matter of fact, to give the keynote address there in Houston and, one of the people in the panel, was a man named Richard DiCicco in New York who was working with David Griffiths, producer of performing arts films in New York.

And, Rick was a great fan of Colossus, and we talked a great deal about Carlos at the time.

We were, setting up this, panel, this seminar on television and during our, negotiation, not our negotiations, but our discussion, shall we say, for this panel.

Carlos died in Paris, and it was Rick who went to David Griffiths and said, gee, I think you know that it would make a fantastic documentary on, this woman in her life and the controversy.

And, David said he thought it was a natural two.

And Rick said, I think, you know, John Ardoin would be the person to write it.

And, so David said, why don't you see if you'd be interested?

And so that's how it really all began.

And, a year later, we have a film.

Here we are.

Yes, exactly.

How did you decide whom to interview?

And.

No, that that that must have been a narrowing down of an enormous gallery of people.

Well, we made it.

We made a, a long list of people that were still active and are still available, who had been close to her either as stage directors, colleagues on the stage, conductors, or simply close friends who had observed her career over a long period of time.

And it was what she would just say time and tide.

It was natural, sort of an attrition that narrowed the list down.

This one was available.

This one wasn't.

I remember we tried our best to get to Joan Sutherland, who had sung with us early in her career in London and who was very, very willing to be part of the film.

But she was off to Australia for three months of opera there, so she was out of the picture.

We wanted very badly John Vickers.

He agreed to be filmed and interviewed, and then he found out that we were doing this with the BBC, and he was having an enormous battle with the BBC.

So he fell by the wayside.

Leonard Bernstein, who had conducted FA at La Scala, was having a very personal crisis in his life at that time because his wife was dying, and it made it very difficult, for him to think of other things.

And so he, was lost to us so little by little, the list sort of narrowed itself down as to who was available, who was, well, who was, would see us.

Even so, we had some very, very close calls, people we wanted to get we almost didn't get, such as Renata Tebaldi, who was the great rival of Carlos for so long or so.

The press and the fans, can see this rivalry, shall we say.

She was very, very reluctant to appear on television.

It wasn't so much her reluctance to talk about Carlos, but, she didn't like the idea of herself on television.

But finally, through, the intervention of, Carlo Maria Giuliani, she agreed to see us in Milan.

And we literally stayed over two more days and got the interview.

The only one that she's ever given on film about Carla.

So it was nip and tuck for a while, but gradually, the whole thing, fell into place, and, well, you still couldn't, use in the film everything that you that you used.

And so we're going to look at a few of those scenes that were not used with some of the most interesting and perhaps some of the most important people.

I'm glad that we have this opportunity to save some of the film, shall we say, because there was, we started off wondering if we had enough and then found out we had far too much.

And some of the, people we talked to had such extraordinary things to say, like Renata Scotto, who was so who saw Carlos, when she was a young student in Milan first and who later sang with her and, Giancarlo Menotti, who had seen her career from the very beginning and who had tried to get her at La Scala before she was a member of the company there to sing in one of his operas and, of course, Tito Gorby, with whom she was so closely associated with, and performances of Tosca, The Barber of Seville and Traviata, and finally our own Nicola of Dallas Civic Opera, who conducted her American debut in 1954.

In Chicago is Norma.

And, of course, made many, many records with her, including her last record sessions in 1969.

Well, we can have a look at those.

And I remember I went to La Scala, up in the LA Dawn.

No money at all.

I remember my teacher gave me the ticket to go, and I was very happy when I had the opportunity to to see and to hear Callas in Norma.

My first opera was Norma, and I was very impressed.

But, by the personality.

And I remember Callas was fat, tall peak.

But when she, move, hands and, push out her voice in, especially in the, in the moment and a very strong moment.

I was crazy about her.

And I said, if I will be a singer, if I will be somebody, I want to be like her.

Maria had a way of even transforming her body for the exigencies of the role, which is a great triumph.

And in, in, in traviata, everything would slope down.

Everything indicated, sickness, fatigue, softness.

You know, her arms would move as if they had no bones, like great ballerinas, in mid-air.

Everything was angular.

I mean, she'd never make a soft gesture.

It was always very.

Even the walk she used to was, you know, like a tiger walking.

I am not a record buff.

I don't like canned music.

I, so I really, I must admit that I had never heard the caller's voice until the first rehearsal.

When she arrived.

And it was a rehearsal, either just the two of us, without even a pianist.

I sat at the piano and played the whole score.

I think, Maria had rightful, I won't say, doubts, but you know who is for?

She knew.

And, I am doing this, very important debut, in her own country, because she was an American, and, I was not Serafin, or I was not Votto or any of these, great conductors.

And we went through the whole score.

Maria said so that we would be more comfortable.

I think it was a test.

I think that Maria had such integrity that if she found in that first rehearsal that, I didn't I wasn't up to par, I don't think she'd have made any bones about it, you know?

Then after that, it was very that that too was very easy, I must say.

It, it was a very good rehearsal and a very satisfying one.

But after that, I mean, it was really a pleasure.

I mean, she is by far the easiest person to conduct that I've ever worked with.

What?

I believe that, she was blessed with with the with the Greek mask.

She, I think more than than the acting and even more than her voice.

It was her presence, which was hypnotic.

She she had a kind of histrionic power just by walking on the stage.

And then I feel that, that she was extraordinarily, musical.

She was a marvelous instrument on which on which, a stage director could express or could could could express himself or a conductor.

She was, I don't think that she herself was a great actress, although many people would disagree with me.

I think it, in the hands of Visconti.

She was a great actress.

In other hands, I thought she was, Let's.

Good.

I'm sure colors were the main industry for a long, long time.

You know, I had to hear people will still talk about Maria Callas as a beautiful and unique, which was crossing the sky over, for a rather short time, but giving light forever to the world of opera.

What was the biggest problem that you dealt with on this film?

Was it was it people?

Was it material?

What was it?

I think it was simply like getting the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle to fit.

I said, I came out of this experience with a tremendous new admiration for opera impresarios everywhere.

The ones that are able to get this singer or that conductor or this stage director all in one spot at one time and, put together something that worked, just coordinating all of these itineraries, these, people in many, many spots of the world and pinning them down long enough to to film them was a tremendous chore.

We, came in to the pergola with some beautiful little theater there as you saw a moment ago.

Behind me.

Scotto.

And, the Alvin and the.

Sorry.

The Alvin Nikolai company was there rehearsing.

They had a performance at 5:00 that day.

And of course, no one had told them we were going to film.

And, they were very sort of hard boiled about it, that this was their time in the theater.

They needed it, and they weren't about to, be quiet.

And, we were getting a little worried as to how we'd make this interview with all this noise going on the stage, the dancers grunting and groaning and stretching and talking.

But, luckily, it turns out that a couple of members of the of the company were great opera fans and recognized Scotto when she came in.

And then when they found out that we were making a film about Carlos, they started policing themselves, several of them telling everybody else to be quiet.

And really, the company kept the company quiet.

And afterwards there was a sort of great love fest between Scott when the members of the company, they invited her to, to their performances, she invited them to her performances.

And so everything worked out just beautifully.

What did you do about film of Carlos herself?

There is, a surprising amount of it in the picture.

Well, there turned out to be we, were afraid at the very beginning that there wasn't going to be enough.

We had sent cables to old television in France and in Italy and in Germany, and it got no replies and, or had gotten negative replies.

And I knew that there had to be more film.

We all we started out with was a second act of Tosca done in London in 64, series of interviews she had done with Large Harwood in England in 68 and some newsreel footage and all.

And, we got to Paris, to begin our filming.

We wanted to go and film the auction of her estate.

Film.

It turned out we had no use for.

But we thought at the time it might be very valuable or exciting.

And, an apartment was set up with us at the archives.

The French television.

They said they had some film.

They didn't know what it was, and they weren't sure if it was any good or.

But we thought we couldn't afford not to see it.

And so we went early one morning, its way out in a suburb of, suburban you lay where all those terrible skyscrapers are now in Paris that are ruining the whole skylight.

And, I'll I'll be more sympathetic about them now, though, after ha They about nine in the morning, we sat down to the projection room and they turned on some film, and it turned out to be the entire 1958 concert, which was her debut in Paris.

And, it had been, shown live over Eurovision.

But by some miracle, the French had kept a kind of scope.

And, it turned out to be some of the most exciting performance film of hers that I had ever come across.

That really gives a feeling for her on stage, this incredible use of her hands and her eyes and that strange, peculiar, loping walk she had.

And you'll see quite a bit of this in the documentary.

There's a large scene from trovatore, a part of Norma, and a scene from Tosca, all from this concert.

Then later we came back to Paris and found, a 1965 concert, with a beautiful performance of the last act aria from Sanam Boola, which closes the documentary.

We even found four minutes of her actually on stage with sound as Norma in Paris in 64.

It's amazing.

We found a silent film in Chicago of her butterfly.

Then in a dress rehearsal, we found silent film in Italy of her last made is at La Scala.

And suddenly, just sort of like a dam broke, interviews with, her voice teacher, Hilda, who is now nearly 90 and, who we were unable to film in Milan, but we found this wonderful interview film that had been made in France and, an interview with Carlos and Visconti.

So the pieces sort of began falling into place.

Well, it's interesting to me that so many of her colleagues were were so helpful.

I do remember, a long time ago, having a conversation with Montserrat Cavalli before she even came to this country in which the the person that she wanted to talk about was Maria Callas, because she had such admiration for her.

And she she felt at that time and I think this was before she'd ever known her.

Well, but that's that's not a thing that you hear very often from one soprano about another.

You know, Patsy, if I could say anything about this experience, it was the incredible generosity of people there, their willingness to change schedules, to, to be with us, to talk about her.

The, the, her influence is tremendous.

The admiration she evokes in people are tremendous.

Talking about Carbajal, we interviewed her during dress rehearsals for Norma at Covent Garden in London, in the dressing room that Carlos had used, and she was very moved to be talking about Carlos anyway, who, as you said, she vastly admires.

But to be in this room brought her almost to the point of tears and, and, brought us to the point of tears, too.

It was so intense, her feelings and her expression of them.

I remember she said that it was ridiculous for her to try to sing a part that Carlos had sung.

She did it because the music was beautiful and that she was asked, but she realized that she was still just a student of Colossus.

And this is for someone of this magnitude and of this importance was a very generous admission.

Miss Gato, too, as you just heard, spoke of the tremendous influence Carlos had on her career.

Was it worth it to Maria Callas?

She was a lonely, unhappy, often difficult woman.

That's such a difficult question.

There are times, you know, when there are people, certain people who are blessed and cursed with an extraordinary gift in which the gift is almost greater than the human being.

And Carlos was one of these people, it was almost as if her wishes her life, her own happiness, were all subservient to this incredible, incredible gift that she was given, this gift that reached out and taught us all, taught us things and about music we knew very well.

But she showed us new things.

Things we'd never thought about, new possible cities.

I think that's why singers admire her.

So I think that's why conductors admire her.

So I know that's why I admire her so.

And she played a tremendous, difficult and expensive price for this career.

I don't think she always understood what she did or why she did.

She knew she had a tremendous effect on audiences and on people, but it was not something that that she could always live with gracefully or happily.

It was.

I once said to her, it must be very enviable to be Maria Callas.

And she said, no.

She said, it's a very terrible thing to be Maria Callas, because it's a question of trying to understand something that you can never really understand.

Because she couldn't explain what she did.

It was all done by instinct.

It was something incredibly embedded deep within her.

Thank you.

John.

Tito Gobbi had this one more small story to tell about Maria Callas.

We close with a reminiscence of Madame Callas in some of her greatest roles as we listened to her voice singing very dirty from La Tosca.

I think Maria was not really a very happy person.

She had some good moments in their life.

I hope she was happy here.

And, but, I never saw her really happy.

And I remember one day in New York, I ask her for dinner with my family, my wife and my daughter, and she said she was alone.

So come would dinner with us.

We had a wonderful dinner.

We enjoyed a lot.

She was playing and acting and making fun with the to and my daughter.

And then when we took her to the lift of the plaza, she said, listen, I am alone.

I am so lonely.

I have not even my little dog to keep company.

Why don't you buy me another ice cream and I stay a little longer with you?

And so we went out.

I bought a little ice cream for all of us, and we had this little cone of ice cream.

And then I said, okay, now I can go and retire.

So I don't think she was really a happy person.

They treat me.

The.

That I did my.

Made me happy to.

Pay for fishing.

My love.

Me?

Yeah.

I can't be bothered with any different ones that are disappearing.

Okay.

When I go to inordinate care.

Yes, senora.

Give everything for me.

David.

More than 400 000 of them to be the beauty for the love.

Wave if me they see.

Me.

Very.

They.

Support for PBS provided by:

From the Archives is a local public television program presented by KERA