Virginia Home Grown

Protecting Our Watershed

Season 25 Episode 6 | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore the importance of plants to our waterways!

Visit a VCU research center on the James River studying riparian buffers and wetlands restoration. Learn how bog gardens control runoff and recharge groundwater with the Albemarle Garden Club. Engage with us or watch full episodes at Facebook.com/VirginiaHomeGrown and vpm.org/vhg. VHG 2506 August 2025.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Virginia Home Grown is a local public television program presented by VPM

Virginia Home Grown

Protecting Our Watershed

Season 25 Episode 6 | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Visit a VCU research center on the James River studying riparian buffers and wetlands restoration. Learn how bog gardens control runoff and recharge groundwater with the Albemarle Garden Club. Engage with us or watch full episodes at Facebook.com/VirginiaHomeGrown and vpm.org/vhg. VHG 2506 August 2025.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Virginia Home Grown

Virginia Home Grown is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(soft entertaining music) >>We can think of wetlands as nature's speed bumps.

They slow water down before it gets to the receiving rivers.

They're also nature's supermarkets.

They produce almost more organic matter than any other ecosystem on the planet.

And they're also known as nature's bird bats.

>>In this time when we just have more intense storms, we've really been able to positively affect this area and keep the water here.

>>Production funding for "Virginia Home Grown" is made possible by Strange's Florist Greenhouses and Garden Centers.

Serving Richmond for over 90 years with two florist shops, two greenhouses, and a garden center located throughout the metro Richmond area.

Stranges, every blooming time.

And by.

(birds chirping) (soft entertaining music) (soft entertaining music continues) (soft entertaining music continues) >>Welcome to "Virginia Home Grown".

Wow, what a gift this month has been, temperature-wise, so different from a typical August.

Today we're thinking about the role that plants play in managing water in the ecosystem, including filtering pollutants, and preventing erosion, and regulating water flow.

They protect our watersheds.

Before we get started, I wanna remind you to send in your gardening questions on our website, vpm.org/vhg.

We'll be answering those a little later.

In the second half of our show, we will tour a unique wetland garden at a park in Charlottesville that has become a popular site for school field trips and community events.

But first, I visited Charles City County to talk with Dr. Ed Crawford, the assistant director of VCU Rice Rivers Center, about a successful wetlands restoration project, and to see a unique waterway, a fresh water tidal marsh.

Let's get going.

>>Back in 1927, this creek was dammed by a gentleman named King Fulton to create a duck pond and a fishing habitat for Berkeley Plantation.

And in 2010, with the help of the Nature Conservancy, American Rivers Organization, NOAA, and the Army Corps of Engineers, we were able to remove the spillway of the dam, and recreate about 70 acres of tidal wetland and a few acres of non-tidal wetland.

>>The Rice River Center is a wonderful resource for your students.

It provides lots of hands-on learning.

So, tell me about that.

>>Sure.

Our focus is on the science and management of large river ecosystems, their watersheds, their airsheds, what goes on above the surface of the water, but also what goes on below the surface of the water, including water quality and air quality.

And it's a place where we can train the next generation of environmental scientists, conservation biologists, and restoration ecologists.

>>And I love the location because I mean, you've got the James River right there, and you've also got now Kimages Creek, which is freshwater, and the James, of course, is brackish and tidal out there.

So this area here is actually a very unique ecosystem that we're sitting in.

>>Absolutely.

So we're at the head of the tides here on the James River estuary, since the tides push all the way up to the city of Richmond.

What makes us unique is that it is tidal freshwater here.

So if you dip your finger in the creek here and take a little sip, it's gonna be fresh.

I wouldn't suggest doing that.

>>No, I'm not planning to.

(Peggy laughs) >>And that makes us a geo-morphologically unique site, because there's lots of work done down in the brackish marshes and salt marshes, and there's lots of work that's being done up in the unidirectional flow of the James.

>>Right.

>>But there's not a lot of science that's done on tidal freshwater wetlands and tidal freshwater ecosystems.

And they're some of the most imperiled and important ecosystems in the world.

And one of the things we did with the help of the Nature Conservancy and American Rivers, was plant about 25,000 aquatic trees and shrubs.

We've planted bald cypress, we've planted river birch, we've planted sycamore, we've planted dogwoods and species like that.

Buttonbush.

A lot of common species that you'd find in aquatic habitats.

They're uniquely adapted both physiologically and morphologically and anatomically to live life in saturated soil conditions.

>>Yeah, I was gonna ask you about that.

What makes a plant capable of living in wetland?

'Cause I know at my house, with all the rain that we've been having, I've been losing a lot of my plants, 'cause they're just saturated.

They can't handle the wetness.

>>Every cell in a plant body, like every cell in the human body, has to have oxygen.

And so even the plants that can grow in water still have to have oxygen in their roots.

So they have these unique features.

It forms what's called aerenchyma tissue.

>>Yes.

>>And that enables a plant to act like a straw from the sediments up to the atmosphere, or from the atmosphere down to the sediments, so they can literally transport oxygen from the above ground chutes down into the roots.

And that's the primary adaptation that many herbaceous and woody plants use in order to get oxygen back down to the roots, so they can carry on their metabolism.

>>In that very wet area.

But not all plants have that adaptation, kind of like in our rain gardens.

>>So in a rain garden, you're gonna wanna put a specific subset of the plants that are out in the environment.

And this subset, of very few plants, actually, out of 22,500 plants that are in North America, are adapted to living life with their roots in saturated anoxic conditions.

>>Uh huh.

>>So if they don't have these unique adaptations, they're not gonna be able to survive in the rain garden.

Many woody species have lenticels that enable gas exchange between the cambium and the outside air.

But in a wetland plant, they're gonna have what's called a hypertrophied lenticel.

So they'll be enlarged in order to help bring air in.

Some of the other adaptations of woody species are shallow roots, adventitious roots, which will form what's also called water roots.

And they'll form if flooding occurs for several weeks or a month, they'll get roots that actually grow not from embryonic root tissue, but out of the stem or the trunks of the trees.

>>Right.

'Cause those cells can differentiate either way.

>>And since when you're dealing with a rain garden or with a wetland and you have saturated soils, plants aren't gonna be able to put a big taproot down too far in the water.

So their plant roots are gonna spread out along the surface to help capture oxygen, but also to help support the tree.

>>Mhm.

>>Ane other interesting feature of wetland trees at least, is the big, flared buttress at the trunk of like cypress trees and tupelo trees and some of the ash trees.

That buttress is like a flying buttress on a medieval church.

It helps support the tree and give it structural support in a habitat where they can't put down big tap roots.

>>It's fascinating, because people are always still wondering what about those knees with the cypress?

And I guess one day we'll know the answer.

(Peggy laughs) >>Well, there's a lot of theories out there, but I think the theory that has the most traction right now is that it's for structural support.

So they spread out and kind of form a little bit of a tiny ecosystem of their own, but it's all for structure to help with tree support in an area where they can't put down a big taproot for anchoring support.

>>Mhm.

And speaking of ecosystems, those trees themselves created their own ecosystem, but the plants all together bring in and enrich, I'll say the wildlife in this community.

>>Oh, absolutely.

You're sitting right now in an ecological success story.

When their dam was here, we had a handful of different fish species that used this site.

Dozens of birds maybe, but once we removed the dam and then restored these wetlands, we've got dozens upon dozens of fish species that are using the site, over 153 different species of birds.

It's hopping with frogs, it's teeming with toads, lots of reptiles and amphibians.

It's a real biodiversity hotspot these tidal freshwater wetlands are.

>>And it all starts with the plants.

>>Right, yeah.

>>The plants.

It rolls back to the plants.

But how many types of plants do you think?

I know you know, how many are growing here.

>>Well, we found 50- >>In Kimages Creek.

>>55 different species of herbaceous plants, and they include perennial grasses such as southern rice cut grass, and annual grasses, such as the northern wild rice that you see right here that's growing.

This is the same wild rice that has sustained the indigenous populations around here for thousands of years, and continues to do so in the Midwest.

We have broadleaf perennial plants like the Pontederia cordata, the pickerelweed and blue flower you see behind us.

We have broadleaf annual plants like arrowhead.

And then there's a host of woody species as well.

We've got cypress, you've got lots of shrubs, and all kinds of woody species of vines that use the site as well, so it has really become an amalgamation of species diversity.

And while the site receives tides like a salt marsh, so it's getting the same subsidies- >>Right.

>>Without the salinity.

So without that salinity, it enables the biodiversity of plants just to explode here, which it really has done.

>>It's fascinating.

People just don't realize the diversity that a wetland provides.

>>Oh- >>And we have forgotten the importance that they play.

And I think here that, you know, this example of taking a lake, removing the dam, and restoring it back to a wetland is one that we can repeat up and down our rivers here in Virginia, and elsewhere along the East Coast.

>>Not only Virginia, but all but all over the country.

I mean, we actually lived in a "dammed nation."

There's over 2.5 million dams, supposedly.

Low head dams and larger dams across the country.

And it is a viable option now to help restore not only stream habitat, but also the riparian wetland habitat.

Help out with cleaning our surface water, with cleaning our groundwater.

>>Yes.

>>And help out with ameliorating the climate, because that's another thing that they do.

They sequester carbon, they help with- >>Tremendous amount of carbon.

>>Yeah, absolutely.

>>Ed, I thank you.

I thank you for really getting down and dirty with wetlands and explaining this.

And for the research that you and the students are doing here at the Rice River Center in Kimages Creek.

(birds chirping) >>The Rice River Center is an amazing living laboratory for research, restoration, and education, primarily focusing on the James River Watershed.

Their work flows beyond the river to influencing public policy.

Now, Amber Ellis, restoration director with the James River Association, is here to introduce us to forested buffer zones.

But before we get started, remember to send in your gardening questions on our website at vpm.org/vhg, or through Facebook.

Well, Amber, we're so happy that you're here today, and I love it when a forest of trees come in and hit the table here.

(laughs) We've got so much to share, but first off, what is a forested riparian buffer zone?

Let's get that straight so people know what we're talking about.

>>Yeah, it's a fancy word, but it's not a fancy thing.

Riparian forest buffers are basically the forests along our waterways, whether it's the stream, river, lake.

Think of those forests that are right along the edge.

>>Right, and what do they do for that water?

>>They are the best thing you can do for water quality, and they're wonderful places for people.

They provide so many benefits to our wellbeing.

Trees, water, and birds are the best thing for our mental health.

And where do you find those?

In a riparian forest?

They also help filter runoff from upland uses.

They help stabilize the stream banks.

They help keep the water cool and at a stable temperature by providing shade.

And forested streams are more able to process pollutants and just have more biological activity.

>>When we think of pollutants, people need to understand that's nitrogen and still phosphates, phosphorus.

Those are our two primary pollutants that we're still putting into our waterways, and that these plants can also pull out and actually sequester right there, if not process it through back into the soil.

So, classic use of, also, a rain garden.

It's all the same principle.

But you've also, in that zone, there are sub-zones, and in those sub-zones go specific plants.

So, what did you bring in with all of these piles?

>>Yep, so when we're designing a riparian forest buffer for a landowner, some of these are 0.1 acres in size up to 20-some acres, so it's large plantings.

But we still think about it in these zones.

You have the wet zone, which is down there.

We'll talk about that.

And then, sort of the lowland that might get wet sometimes- >>But not very often.

>>But not very often, but it has to tolerate that flooding.

And then, you have upland, which may flood every now and then, but- >>Generally dry.

>>Needs to be able to tolerate being dry for a period of time.

>>So, I think I see you've got one of your favorite for the uplands to start with.

>>Yeah, so when people think of fruiting native trees, they think pawpaws.

But another fun one is the persimmon.

You can see it's already starting to fruit, here.

It fruits in fall through winter and wildlife love them, so that's a great one.

>>Yes, and I will tell people, do not eat this until a frost has fixed it.

(laughs) >>Correct, it needs to look almost like, wrinkly and not great, yeah, and that's when you wanna eat it.

>>So, it converts those starches to sugars, or you'll pucker up.

But I see some oaks in there, and I see some dogwoods and other things, so common trees in our landscape, or the uplands.

>>Yeah, and dogwoods are a great one on the upland part, because it's usually along the edge of the buffer where people can see it.

So, that one's a great one.

>>Okay, but in our next zone up, your other favorite one is also a fruit-bearer.

And I think I'm gonna put it upside down so people can see it more.

Let's see if we can get it over here.

But this is more of a shrub.

>>Yep, this is a spicebush.

Very common understory shrub in our riparian forests.

You don't have to do much to get these things growing and going.

You can see the little red berries starting here.

And you'll know it's spicebush, if you're wondering, you can grab the leaf and smell it, and it will smell.

It has a very spicy smell to it.

>>It has a wonderful smell.

But also in this pile, we have some black walnuts and some other types of oaks, such as our willow oaks and some, I'll say hornbeams and such are in here.

But then we get to the wet area and we get to one of my favorite plants, which is right through here.

>>Yeah, this is a really fun one.

This gets to be a large shrub, the buttonbush, and you can see why it's called that with these really fun flowers that form, here.

Butterflies love them.

They love wet areas, do really great.

And just, those spots where you can't get much else to grow, these will do great.

>>Yeah, really super wet areas.

You'd be surprised.

But in this pocket here are also red maples, and even some lower species like our, I'll say bald cypress, and even our sycamores, again.

>>Yeah, sycamores are, out of riparian forests, that is really the champion tree of the riparian forest.

They grow really fast.

And when we're thinking about what species to plant, we love to plant a lot of fast growers and then mix in some slow-growing things.

>>Super, well, we've got more to talk about.

>>Yeah, keep going.

>>So, I'm gonna keep going, 'cause planting these is not like, typically, what we think.

And I'm gonna start off with sharing the tools.

So, could you tell us about this wonderful tool?

We've got two minutes, so let's just quickly talk about it.

>>Great.

Yep, so we usually, most of our buffers go in by contractors, but we do use volunteers, too, and this is a great shovel to use.

We plant these as bare root seedlings, so you've got a long root that you're just trying to get a skinny hole, just big enough for that root.

So, these are great.

>>Excellent.

And this is a good way for chopping away the brush.

>>Yep, that helps take the sod off the top before we dig the hole.

And then, these are, if you see these on the side of the road, these are tree shelters.

Again, we're planting bare root.

These are great at protecting it from deer rub or voles, and they also serve as a greenhouse to help extend the growing season on either end.

>>Excellent.

>>And help to know where they are when you're doing maintenance.

>>Season extender, love it!

But then, you have this mat, here, and it's under everything else, and I hope people can see it.

But what is this one for?

>>This one, so part of the maintenance for these is that we typically spray around these tree shelters to get rid of some of the competitive vegetation.

But in some cases, that's not a great fit, so we'll use these coconut fiber mats.

>>That would be great, and reduces watering.

>>Yep.

>>And reduces weed.

Well, this is great.

So, you plant hundreds of trees at a time.

>>Yes, since our buffer program started in 2019, we've planted over almost 1,300 acres, and we plant 300 trees per acre.

So, thousands of trees.

>>What part of the James River are you planting most around?

>>Yep, so our program covers the Piedmont, like Middle James and Upper James.

And by far, the most buffers we've installed are in Albemarle County.

>>Well, Amber, I wanna congratulate you, the James River Association.

This is awesome, and what you're doing to preserve and conserve our river.

So, thank you.

>>Great, thank you.

>>And now, we're getting ready to answer your questions, but first, Randy Battle has some tips to share for starting seeds and using water in the garden responsibly.

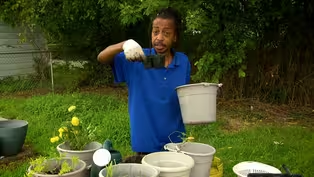

(light percussion music) >>You can grow your garden 365 days a year, but one of my favorite times of year is the summertime because you can grow all different types of crops.

Today what we're gonna do is start some seed starting mix, and I'm just gonna show you how I make my own seed starting mix using some old soil that I had from previous years.

And this particular soil right here, as you can see, I'm just taking it right out of this container, uh, uh, okay?

And we're just gonna put it into the sifter, right?

And I have a sifter just for my garden.

And what I like to do is take my sifter, and I take a regular old container, and I wanna sift it just like so.

(soil rustling) You can just sift it just like so as if you're cooking or if you're making something in your oven.

But yeah, I love to make my own seed starting mix.

And what you will get, you will see (soil rustling) how nice and soft that soil is.

And what I like to do is just take a seed starting container, (soil rustling) pour my homemade seed starting mix in there, okay, okay?

(soil rustling) Yeah, we take what we have and make it work.

And then you wanna take just a seed.

These are some green beans.

I'm just gonna drop the seed right into the container and take a little bit more of my seed starting mix and pour it right over.

It's not rocket science, you guys.

Make it fun.

Make your garden fun.

Watering is one of the most important things that you wanna pay attention to.

You don't want to over-water and you don't want to under-water.

One way to find out if your plants need water or if your soil is dry is use the finger test.

And what I like to do is just gently take a finger and push down into the soil.

You will feel if it's moist or if it's dry.

If it's dry, add a little water.

If it's moist, you should be good to go.

I like to water around my root system instead of pouring water directly on the leaves, because if you do that, you can get a lot of fungi, and mold, and pests.

What I like to do is take my time and sprinkle a little bit here and there, use my finger stick to make sure it's moist, okay, okay?

Live, love, laugh, grow stuff, and eat it.

>>And now it's time for our favorite part of the show, when we get to hear from you.

Make sure to send us your gardening questions through our website at vpm.org/vhg or Facebook.

Amyrose Foll has joined us to be part of the conversation.

So, welcome, Amyrose.

We're so glad you're here.

So let's get started with the questions.

>>Oh, my gosh, thank you so much for being here.

What kind of maintenance is involved in all of this?

And again, thank you so much for being here, and aside from the maintenance, what are the kind of tidbits do you have for us today?

>>Yep, so maintenance is, if you do any kind of gardening, you know that is the most important part.

>>Yes.

>>And so, our James River Buffer Program, we help with the first three years of establishment maintenance, which includes those tree shelters, just fixing them once a year, straighten 'em up, controlling invasive species, kind of conservation, mowing between the rows just to allow access and keep down some of that competitive vegetation.

And then, especially right around the tree shelters as well.

>>Very nice, so what kind of other programs are there for landowners or what kind of information can you give us on that?

>>Yep, so right now, there's a ton of different types of programs.

No matter what type of property you have, there's probably a program that could help you plant a buffer.

So there's our James River Buffer Program, which is open to any kind of site.

There's the Virginia Agricultural Cost Share Program through your local school and water conservation district if you're a farmer.

There's the Virginia Conservation Assistance Program if you're more in an urban lot and maybe don't have enough like a lot of space.

So lots of opportunities, and we actually have a little tool that we created to help people figure out what program's a good fit for them.

>>Oh, very nice.

>>That's awesome of the James River Association to do that.

>>I can't believe you, like- >>mm-hmm.

>>That's amazing.

>>That's the hardest part.

Like, where do I go?

>>I love that, yeah.

>>Who can help?

>>I don't know, my 14-year-old could probably help with that.

(everybody laughs) Just with the creation of that.

So, Craig from Mechanicsville rode in, and he wants to know what are your thoughts on relative to controlling invasive plants near wetlands, for example, a stand of bamboo that's encroaching on a swampy area?

And then he wrote, "I would think herbicides would be off the table as to ensure the health of the nearby ecosystem," which is, of course, very important.

>>Yeah.

>>Mm.

>>How do you balance that?

>>It is for every project we're balancing 'cause the goal is never gonna be to eradicate it all.

But how can you manage it in a way that's going to create a space for the most biodiversity of life to happen, is the way that I think about it.

And it's not gonna be zero invasives.

But I would recommend that he search to find somebody that is a certified pesticide applicator because they're gonna know what's safe to use there and what's not.

>>Oh, okay.

>>There are products available.

>>There are.

>>That he can use on the property to take care of the bamboo and have it be near a wetland, yes.

>>Yes.

>>That makes me nervous.

>>It does.

>>But it's good to know that there are experts out there that can help us, you know?

>>Yes, read the label.

>>Yep.

(laughs) >>And Blue Ridge, Blue Ridge PRISM is a great resource for people in Virginia.

>>What's it called?

>>Blue Ridge PRISM.

Okay, at Charlottesville.

>>Yeah.

They have great fact sheets on different types of invasives, and will tell you, mechanical removal, herbicide, different ways to do it.

>>Oh, very nice, very nice.

Susan in North Chesterfield said that she has a very large beach tree that she would like to have evaluated by an arborist.

What's the best way to find a good arborist that's a good fit for her?

>>Well, they can go to the International Society of Arboriculture Support's of Find My Arborist Program.

>>Really?

>>And they can go and find it through there.

>>I love learning from you.

>>Yeah.

(laughs) >>I learn from you every time I see you.

What was that called again?

>>It's called the International Society of Arboriculture, and it's called Find My Arborist.

>>Oh, that's wonderful.

>>Mm-hmm, it is.

It's a great program.

>>And I know this is gonna be a topic that you're really gonna love.

What plants would you recommend that also work for really great erosion control?

>>Hmm, it depends on the situation.

I don't know where they're at, but if you're on a creek, a really cool method is live-staking in our riparian buffers.

So, some of the species that we showed today, actually, you can get as live stakes, and these are just cuttings.

If you have them, you can just cut a little branch, and then it just goes right into the stream bank.

>>Mm-hmm.

>>Buttonbush, elderberry, ninebark, various ones can help with that.

And it's pretty cheap and simple.

>>Yeah.

>>Oh, elderberry.

>>'Cause it stays consistently moist.

It's gonna be a rooting chamber.

>>Yeah.

>>Yeah, elderberry will root like nobody's business.

>>I've been canning elderberry syrup for the last two weeks.

>>I've been chasing the deer off of mine.

(laughs) >>Oh, no, I'll bring you some next time I see you.

>>Thank you.

(laughs) >>Okay, this is something that, okay, because I don't live in Richmond, I live a little bit far or far-field, and it comes up in our area all the time.

Brian wrote in, asking, will the buffer zones reduce E. coli bacteria in the river area because we have campgrounds where I live.

I'm still here, in our area in Central Virginia.

But we've got a lot of cattle farms where I live.

So what would you, what do you... Or what are your thoughts on that?

>>100%?

Yes.

>>Really?

>>A lot of the projects we do, we partner with our local soil and water conservation districts.

There's record funding to support landowners right now to exclude cattle from those streams, provide alternative watering sources, and then we come back in and plant the trees.

>>Yeah, oh really?

>>Yeah, mm-hmm.

>>That's amazing.

I love that.

>>Yeah.

>>I had no idea that it could reduce that because we always get warnings in our area not to go onto Lake Anna, and you know, in a lot of the campground beaches.

>>Yeah, that's hard.

>>Which is a bummer because, you know- >>It's recreational.

>>Yeah, and it's beautiful.

All right, so how can people get involved with the James River Association?

>>Oh, so many ways.

If you go to our website, which we'll have a link to, you can volunteer.

If you're interested in our Riparian Forest Buffer work, we have a program called the Riparian Stewards, and we train them, and they come out and help us do survival checks and replant and care for them.

We invite volunteers to come out and plant trees with us in the fall, in the spring.

But we also have a Water Quality Monitoring Program.

We have our RiverRats Program.

Lots of ways to volunteer.

>>Lots, I love that.

>>Yeah.

>>I want to do this.

>>Yeah.

(laughs) >>Oh, my gosh, can I volunteer?

>>Yeah, so many ways.

>>Oh, my gosh, this is wonderful.

>>Yeah.

>>And, okay, so I love that.

I'm sorry, now- >>They're turning- (speakers talking over each other) >>I wanna come do this with you.

Oh, my goodness, I'm sorry.

So Sharon in Church Hill asked how can I keep many varieties of hostas green and healthy for as long as possible?

I actually have transplanted some hostas recently, and it has not been good.

I don't know the deer problem that you're talking about.

Like your elderberries.

>>But the heat.

>>The heat.

>>They've been so yellow and terrible.

>>Yes.

>>Even in the shade.

>>Okay.

>>I don't know what to do.

>>We just we're talking about how trees absorb nitrogen.

Here we have a situation where we are having nitrogen leached from our soil from all the rain we've been having.

Yeah.

>>Which is causing our plants to turn yellow.

But the other thing is, is hostas are a full shade, cool-seasoned, you know, cooler-loving plant.

And it's the heat, they don't like it.

So if it gets a little bit of sun, it's like very unhappy.

>>Yeah.

>>But give it too much rain, she needs to fertilize it.

But also understand, cooler days are coming, and things will get better >>And also, I'm very worried about mine.

(chuckles) >>Yeah, just keep loving them.

So we got just seconds for a short one, so.

>>Okay, so also, how can people, what is the most need that you have for people getting involved as far as volunteering for these days?

Whether it's planting trees or donating, whatever.

>>I would love our... Well, donating to our program is always helpful, but... (Amy laughs) I know, but Riparian Stewards, that's a great program.

Just more hands to help with the maintenance and caring for them.

That's a never-ending need that we have, and it's fun.

>>Riparian Stewards.

>>Yep.

>>And that's here in the Richmond Area?

>>Yeah, we have all across the watershed.

>>Oh, wonderful, thank you so much.

>>Wonderful.

>>Is there anything else you'd like to add?

>>Just thank you.

And anything people are taking away just now, you know, what a Riparian Forest is, and spread the word.

>>Exactly, so.

>>Yep.

>>And that's all the time we have right now, but we look forward to answering more questions later in the show, so keep them coming.

And again, Amber, thanks, you've showed us so much.

We're gonna think of planting trees a little differently, and look at 'em differently along our waterways 'cause they are our filters, so.

And next, we're going to visit The Bog Garden at the Booker T. Washington Park in Charlottesville.

The garden is the project of the Albemarle Garden Club, and Amyrose met with Dana Harris there to see why that spot has become a favorite with so many in the neighborhood.

So, let's take a look.

>>So we are in Booker T. Washington Park, and this is a microclimate wetland.

We in the Albermarle Garden Club refer to it as the Bog Garden because it's just kind of a sweet, fun name, but it is really wet, fairly stagnant.

And so if you had to step in there right now, you would probably sink about four inches and your shoes would definitely be wet.

>>Ah, it is magical in here because of the dappled sunlight and the shade.

It's really kind of a little oasis here in Charlottesville.

>>Yeah, it's a nice little quiet corner.

And in my time working in this garden, we've seen more and more people use it, which is lovely.

The city has created some trails around and so it actually has gotten much more used.

>>So tell me a little bit about the plants that you have arranged in here.

>>Yeah, so we really focus on natives and I would say there was a great deal of invasive removal that happened before any of these plants really took hold.

But as we've spent years taking out invasives, we've had good luck with planting plants.

We have a fern that's called sensitive fern, turtlehead.

There's a New York ironweed.

This is quite a grove of ostrich fern and there's some Joe-Pye weed in the distance.

We've never planted Joe-Pye weed in my time here of 10 years, but I think it's clearly happy here and has self-seeded.

>>It's great for the butterflies too.

What is that lovely splash of color that's in the center there and along the edge?

>>Yeah, that is cardinal flower and that really is quite spectacular this time of year, I think.

>>Of all of these plants in here, what's your favorite?

>>Well, right now you have to love the cardinal flower, right?

My opinion changes every time I'm here, depending on what time of year it is.

I would say in the spring, we have beautiful ephemerals, we have tons of woodland geraniums and blue bells, and, you know, that whole hillside is just covered with blue bells, which is really spectacular.

But this time of year, it's hard to think that it's much better it's hard to think that it's much better it's hard to think that it's much better than this cardinal flower.

We have to pay a lot of attention to runoff.

As you can see, you know, this beech tree here has had some erosion and we've researched and decided that lady ferns, which is the ferns you see here, are really the best that we can find to match the soil water and they really hold the soil quite well.

>>It's beautiful.

That is a majestic tree.

Absolutely wonderful.

So how long did it take you to get this established here?

It seems like a lot of work.

>>You know, it has been a lot of work, and while I'm the one standing here, it has been a real community effort.

The Albemarle Garden Club hosts a work day a month.

We have probably anywhere from like eight to 12 people work and the city supplies us with a tarp and we put all of our debris, any invasives on the tarp and they come and take it away.

So it's taken us about 10 years to really get this going.

And I would say we now aren't spending as much time on invasives and we're able to spend more time helping the community find ways to be here, helping school kids come and support field trips here and do things like that, which is really sort of another fun thing.

>>So what was the most challenging invasive to remove from this area?

>>You know, I think some of the, like, Japanese grasses, They've been really hard.

It was actually beautiful.

It was this very chartreuse-y green, but it has the oddest root structure and it has been virtually impossible to get completely rid of.

We are winning the battle, I would say.

These sensitive ferns have really helped as they've developed.

You know, these were just little tiny plugs.

So, you know, it's an ongoing thing, but we don't wanna spray anything in here that's toxic.

So we do just pull the weeds when we see them and hope that when we plant the natives, they just are able to fight off some of the invasives and that seems to work.

English ivy is also a hard one here.

It just doesn't even seem to matter that it's really wet soil.

You would think they wouldn't like to have wet feet, but they don't seem to care.

And I would say we also, unfortunately, are fighting the fact that in this park in the '70s, I have been told that Parks and Rec planted 7 to 8,000 plugs of English ivy to try to keep erosion at bay.

So we now know no one would ever do that, but at the time, that seemed like a good idea.

>>This is a pollinator hotel.

that you guys have built?

This is a big hit with the kids that come through here.

They love this, you can even see now Theres some... >>Its being inspected by something, yes!

It is, it is!

Some things!

And this was a project that the Albemarle Garden Club took on about eight years ago, and we had a great metalsmith guy come and build this structure and it was really quite an effort to get it into the ground.

>>So this is so beautiful.

What are the ecological benefits of this garden area?

>>Well, I think primarily because it is a microclimate wetland, it serves the purpose of slowing the runoff from higher elevations down lower.

It captures the water, the water gets into the ground table and doesn't run out into the street.

It's housing and food and water for bugs and creatures alike, and that is a benefit.

And I would say the water gets cleaner because these plants are here.

It basically supports all these plants.

>>So you mentioned community in the garden.

It sounds like you have a lot of great things going on and events here.

How can other people get involved?

>>So I think this park gets used a great deal.

We have spent our efforts on a couple of things.

We wrote a grant and received a grant from the Garden Club of America to host a community day here, which we've done the last three Octobers.

And that has really been, it's been called Down by the Bog and it's really been a family day, family fun day, intended to bring people to this place and to educate them.

We have frogs and little kids count the number of frogs in the bog and we've got all sorts of sort of just nature play.

And it's done in partnership with about four or five other non-profits in town.

And we've had as many as 300 people show up.

People from the Garden Club bring flowers from their garden and the kids make little bouquets.

And it's been a fun event and a great way to get people to learn about what is a wetland, why it's important.

We also are lucky that this site is within walking distance of five different public schools and it's used often as a science field trip.

And we've hosted second graders here to talk about pollinators, which has been really fun.

We've hosted seventh graders here to talk about water and ecology and climate change.

And so it's always fun to have young people move through this space and the questions that they ask and the things they're interested in are always sort of humorous.

>>That is wonderful.

Thank you so much for having us today, and thank you for sharing this beautiful garden with me.

>>Oh, you're welcome.

Thanks for having me.

>>The diversity of plants and wildlife in this special oasis proves even small wetlands can make a huge impact on the community and the environment.

And now we're joined by Krista Weatherford from Maymont to learn more about some of the critters that thrive in ponds, bogs, and wetlands.

You know, I'm always happy to welcome my former colleagues from Maymont to the show, and especially this season as we celebrate 25 years of "Virginia Home Grown."

Maymont has been represented on the program countless times over the years.

And so I thank you for being here today, Krista.

>>Well, thank you for having me.

>>Certainly.

But again, before we begin, we want you to send in your garden questions through our website, vpm.org/vhg, or through Facebook.

You know, Krista, I know your specialty, you know environmental education, and I know that when people are putting in water ponds and things like that, they're thinking about the plants.

They're not thinking about the critters that are coming.

So who usually comes and joins in, I'll say in the fun of the plants in the water when they put a pond in?

>>Well, there's actually a lot of diversity that will be attracted to that space.

It could be macroinvertebrates, so some of our dragonflies and beetles and things like that in the water.

But also you'll get a lot of our amphibians.

And amphibians are actually an indicator species, so they help us to understand the health of our waterways and things like that.

And they are actually, there are a lot of them that are in decline right now because of habitat loss, because of pollution in the water and things like that.

And so these guys need homes.

And so what a better way for us to create these spaces for them and invite them to come and live with us.

>>And also now that we know they're an indicator species, if we do it right and they come, we've succeeded.

>>That is definitely true, yes.

In fact, you might get more than you bargain for.

(both laughing) >>Well, that's a good problem to have.

>>It is, it is a very good problem.

>>Well, you've brought in some samples of some of our favorite critters.

>>Yes.

>>Yes.

I'm just glad they're not all croaking right now.

(both laughing) >>Well, and you know me, wherever I go, I've got some friends that I bring with me.

>>Absolutely, absolutely.

Well, let's start with our dry land friend, because he's out and about and being sociable right now.

>>I know, isn't that wonderful?

Yes, so we have a little Fowler's toad here, and Fowler's toads are, they're an indicator not only for water quality, but also soil quality.

Because they are a terrestrial being and they like to be in the soil and they'll bury themselves, that's one of our problems that we had earlier, is that he was hiding so well in the soil.

But their skin is very thin, and so it absorbs the moisture from the water or from the soil as well.

And so that has another way in which that that transfer of air and water through their bodies makes them an indicator species.

>>But if you're a person who maybe puts a lot of pesticides down, you won't get our little friend here.

>>Right, so if you're not seeing a whole lot of frogs or salamanders in your area, then there might be something wrong with your, either your soil or your water.

>>And consider your cultural practices.

>>Exactly.

>>Exactly.

Well, we're gonna move from land to water so he can crawl back underneath.

>>Okay.

(both laughing) >>Hide himself.

And here's another little guy.

Who do we have here and where is he?

>>Yes, so this is one of our little leopard frogs.

Let me see if I can help him to make his debut.

He is right over here.

And so leopard frogs are another one.

>>Just right in there.

>>Just right there.

>>Let's turn the... >>Can we turn it that way?

>>Yeah.

>>Yeah, there we go.

So leopard frogs are another one that are a common species that you would find in your water.

So these guys, as all of these amphibians, they will actually go to water and they will lay their eggs there.

So you might see some of the tadpoles.

So this guy is most likely from the spring then, and he's growing up a little bit.

So that's why he's so small.

But they can get to be about that large.

>>Oh my, yes.

Wow.

>>Pretty good.

>>That is pretty good.

He's so young and so active.

>>He is very active.

And of course with frogs, one of the things about them too is that not only are they a prey species, but they're also a predator.

>>Oh.

>>So amphibians are great for controlling, you know, different mosquitoes or other things that might be in that area.

So this one is a Pickerel frog, and he's quite cute.

He's got dorsal lines down his back, and then two sets of spots all the way down.

And so these guys are another one that really like to be in the water and around the water.

And they have some very fun croaks noise that they make.

They sound like a demented clown chuckling.

>>(laughs) I have them at my house.

>>It's a demented clown.

>>That's a good description.

And then the star of the show.

>>Yes.

>>Yes.

>>We have a green frog here.

And he's one of our nice big species.

But these guys are, again, found in waterways.

The large circles on all of these guys are their ears, so that's their tympanum.

And so that's how they're able to hear.

But the males will do a lot of croaking during the springtime, attracting those females.

And then of course, they're laying their eggs in the water.

>>Yes.

And we can watch those egg masses in the water.

>>Yes, big egg masses.

And that's another great indicator that you've got good water quality.

>>So kind of if you build it, they will come.

>>Oh, definitely, definitely.

>>And that's exciting because they need the habitat.

>>They do, they do.

>>You convinced me to put that water garden in.

>>(laughs) I know.

>>Thank you.

Well, Krista, thank you so much.

I really appreciate you coming in and sharing your expertise on our amphibians and just talking to us about a few of the frogs for our bogs and water gardens.

Next we're going to answer more of your questions.

But first, Dr. Robyn Puffenbarger shares, why adding a water feature to your garden is a great idea, whether a small fountain or a large pond.

(lively shaker music) >>Many of us who live in Virginia have a pond, a stream, lake, or other natural water source to enjoy in our backyard landscapes.

But many of us also live in small places or places that just don't have access to water.

And so one of the things we can do is bring water to our landscapes.

That could be a small feature, like a self-contained fountain or little pond system that you put on your deck.

You'd plug it in and have the sound of water, and that moving water might attract birds to your back deck.

You can also put a much larger pond in, like the one that's behind me, that's dug in, and then deep enough to support fish and plants.

This particular landscape is really enjoying a mix of sun and shade, and one of the things that's very flexible about water features is that they will do well in either spot.

Depending on how much sun you have, you may need to add water more frequently if you're in full sun and make certain plant choices to make sure that they, in the water and around your pond feature, will tolerate that full sun.

Like the water lilies, which have an array of colors to choose from when you're making purchases or finding them.

To cardinal flower, which is a Virginia native that is super deep red, pickerelweed, which is a light purple and also native.

Fish are a wonderful addition to a pond, giving lots of color and life.

But if you're not interested in having fish in the pond, don't worry, if you don't have them, both frogs and salamanders will occupy your space, laying their eggs.

They usually avoid places with fish because the fish are predators for them.

So you can have this natural landscape, natural creatures come in.

Once you have that water and sound, you're going to see mammals, like raccoons, opossum, and deer, if they're in your neighborhood, maybe drinking, which is a wonderful thing to see.

And if you make part of your water feature shallow, so not very deep, maybe just an inch or two deep, then you'll see your birds start to bathe and drink.

Most birds won't enter water that goes over their feet, they're very fearful of drowning.

So having that little spot where it's nice and shallow for your birds, you'll really enjoy getting to see them as well.

So water features have all sorts of added benefits for your home and garden landscape.

So think about anything from a very small, little fountain you could add to a much larger pondscape if you've got the space for it.

You'll really enjoy the sound of the water and all of the interests that it attracts.

Happy gardening.

>>So when we think of water, we need to also think of plants.

And plants are key to reducing runoff, capturing pollutants, controlling erosion, and filtering water.

Our waterways are peaceful living systems in which plants and wildlife sustain each other, creating a connected environment.

As the built environment expands, we need to promote sustainable practices to maintain this delicate balance.

So, and now we're gonna take more of your questions, so let's go ahead and please send them on in.

So let's see what we have now.

And Krista, I'm gonna share with you, you know, one of the questions is, you know, Maymont, you know, does it still participate in FrogWatch?

And if so, you know, what are the, I'll say, how can people get involved?

Do they just, yeah, contact Maymont?

>>Yes, actually, we typically will have a training session every spring.

So usually around March, April timeframe.

And we, with the training, it's not only learning how to identify the frog calls and things like that, but how they can actually find a local source themselves so that they can go out and do the frog monitoring.

So- >>Citizen science.

>>It is, and we appreciate all of the data that we can get.

>>Are there known frog areas in, I'll say mapped throughout Virginia, that if people who live, say in the Piedmont, they know that they can, I'll say run into larger populations in one area versus another, or?

>>There are, but typically if like there's a quarry near my house and the frogs are so loud, so a lot of times it's just kind of wandering around at dusk time and listening for those frogs.

And once you've identified a location that's close to you and convenient, then you can add that to your monitoring sites.

>>Oh, that's great.

Is FrogWatch a nationwide program or?

>>It is, actually, it is.

So we are ones that do the training, but also Virginia Zoo does it and a lot of other organizations throughout Virginia.

>>So there's many opportunities.

>>There are.

>>Sounds great.

Another question is, we can travel easily, but how far can frogs and toads travel, say to a new source of water or to find a source of water?

>>Well, so our habitats are so fragmented.

>>Yes.

>>So with having a lot of roads and things like that, it makes it very difficult for these frogs to be able to actually travel.

You'll sometimes see them squished on the road and things like that.

And so hopefully they'll find water.

But it can be very challenging for them.

And of course then they're susceptible to a lot of predators that are out and about as well.

So the amount of travel that they can do is really up to luck.

You know, how much they can get to, and how quickly they can get there.

>>Yes.

There's no little land bridges for frogs.

>>There aren't, there aren't.

>>What's the biggest predator for frogs here in Virginia?

>>Let's see, we have a lot of snakes and things that will actually eat amphibians, in particular, your frogs, but also a lot of birds.

A lot of birds will eat them as well.

>>Really?

>>Some of the larger birds?

>>So larger birds, even our barred owls and red shouldered hawks, they'll eat frogs and toads.

Salamanders.

So, yes.

>>Really?

Oh my goodness.

>>I didn't realize that.

>>Yeah, they're living in that same habitat, that same ecosystem.

And so yeah, they'll prey on them.

>>Interesting.

Well, it does make sense.

Yeah, yeah.

>>They can stay away from our chickens.

>>Yes.

>>And go on.

(group laughing) >>My other question though, is native plant wise, you know, so many gardens are, and people are trying to switch from non-native plants, which have been around, you know, for a long time, can't diss it, but through changing over to native plants, do you think as this switchover changes, you know, more of the amphibians, more habitat will be created, but where would it start, with the frogs, with, you know, salamanders, you know?

>>Yes.

So hopefully yes, people are going to, as they put in more of these native plants, it will invite more native species to come into those areas.

And it can start in a lot of different places.

It depends on what you're planting, where it is, and what kind of water features and things that you have in that area.

Even if you're putting in a bog or putting in some kind of a water feature, if there are a lot of fish, then they're gonna eat the tadpoles.

And so you're gonna have to be careful of which one do you want.

You know, do you want the fish, do you want the tadpoles?

>>What's the balance?

>>Right.

And what's the balance between them?

>>I have to tell you the story.

My kids were little and we had that little blue baby pool.

We all know that blue baby pool.

Well, we went on vacation, it had rained a lot.

We came back to tadpoles swimming.

Hundreds and hundreds of tadpoles in the blue baby pool.

And we had to- >>Did you hatch them?

>>We, yeah.

We had to scoop 'em up and move into our neighbor's pond and while they were being put in, the fish were coming up and eating.

And the poor girls.

And we had to explain the circle of life, right?

But we tried so hard.

I know some, I know many survived, but to come home to see hundreds of little baby tadpoles swimming around in that little baby pool was quite funny.

>>Well, and that's why they have so many babies, right?

Is because they know that some are going to get eaten.

So they have large masses of eggs.

>>They're fascinating when you can start to see them all moving.

You know?

I love that.

>>Seeing them start wiggling in the gel, it's so cool.

Yeah.

Well, Amyrose, do you have a pond on your farm?

>>I, well, we have kind of a canal thing.

My farm, the headwaters of the York River watershed actually come outta the ground in my yard.

And so we've got a canal, a creek, and a swamp area where I've got my own bog garden that I grow river cane and katniss and arrowhead and whatnot, blue vervain, all sorts of great, bottle brush, which is one of my favorite plants.

I love that we have that here today.

And we have many, many frogs.

It's loud at my house.

>>Oh, I bet.

>>And unfortunately, I learned the hard way that you cannot put those frog eggs into a fish tank.

And you cannot let your children put them in a fish tank with crayfish.

It's a disaster.

But I do have a pond and we have tons and tons of frogs and toads.

And actually, I'm not originally from Virginia.

I've been here.

I'm a southerner at heart.

I got here as fast as I could.

The army stationed me down here.

But I had a rude awakening to frogs the other day by getting barked at by the largest frog I've ever seen in my life underneath my oak trees, in my herb garden.

Thing was this big.

Had thigh on it like this.

But, it was shocking at first, but it was really amazing to be able to pick him up and take him over to the little swampy area where I've got my duck potatoes and release him.

They're fascinating.

It's absolutely fascinating.

My grandmother used to always say, you wait until the snow falls on the peepers once to plant your first tender, or to wait to plant your first tender vegetables in the garden.

So I'll never forget that.

>>Never, ever, ever.

It's a good one.

I love your story.

Thank you, Amyrose.

That's great.

It really is.

And I know we have lots of experience with frogs, so, I'm just encouraging people to really go out and put in some water features or just go explore a nearby one because frogs are so fascinating.

They really are cool.

So, well, I wanna say we're out of time.

And Krista, thank you so much for being with us.

It's been a joy to have you.

Usually we have plant people, so it was fun to have a critter person.

(group laughing) And Amyrose, thank you as always for joining us.

We appreciate it.

And I wanna thank all of our guests today and thank you for watching.

We hope you better understand the role plants play in protecting and supporting our waterways, and consider steps you can take to protect these important ecosystems.

And remember to sign up for our monthly newsletter at vpm.org/vhg for gardening information and advice from me and the team.

Also, our Facebook page is full of gardening tips, so be sure to visit us there too.

You know, I look forward to being with you again soon.

And until then, remember, gardening is for everyone, and we are all growing and learning together.

Happy Gardening.

(peaceful music) (peaceful music continues) >>Production funding for Virginia Home Grown is made possible by Strange's florists, greenhouses, and garden centers.

Serving Richmond for over 90 years, with two florist shops, two greenhouses, and a garden center.

Located throughout the Metro Richmond area.

Strange's, every blooming time.

And by... (birds chirping) (calm music) (calm music continues) (calm music continues) (peaceful music)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 7m 52s | Discover native plants that thrive in wetlands (7m 52s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 6m 28s | Discover why healthy forests improve water quality in streams and rivers (6m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 5m 32s | Learn identifying characteristics for common amphibians in Central Virginia (5m 32s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 3m 3s | Create a homemade seed starting mix and get waterwise gardening tips (3m 3s)

Water Features for Home Landscapes

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 2m 57s | Discover the benefits having a water feature in your garden (2m 57s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep6 | 8m | Learn how a dam removal project created an ecological success story (8m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Home and How To

Hit the road in a classic car for a tour through Great Britain with two antiques experts.

Support for PBS provided by:

Virginia Home Grown is a local public television program presented by VPM