Antarctica's Survival Guide for Mars Explorers

Clip: Season 25 Episode 16 | 13m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

How did the extreme Antarctic winter affected the Belgica's crew?

In 1897, the Belgica set sail for Antarctica on the first true science mission to the end of the world,. But within 200 days, the crew found themselves trapped in sea ice, battling disease and insanity during the unending polar night. What can their trials teach us about maintaining sanity in the harsh environments of space as humanity plans for it’s first crewed mission to Mars?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Antarctica's Survival Guide for Mars Explorers

Clip: Season 25 Episode 16 | 13m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

In 1897, the Belgica set sail for Antarctica on the first true science mission to the end of the world,. But within 200 days, the crew found themselves trapped in sea ice, battling disease and insanity during the unending polar night. What can their trials teach us about maintaining sanity in the harsh environments of space as humanity plans for it’s first crewed mission to Mars?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- When the Belgica left port for Antarctica, carrying the first true science mission to the end of the world, its crew likely never imagined that within 200 days, their expedition would be trapped in sea ice in a seemingly endless polar night, where disease and insanity slowly set in.

The first humans to travel beyond Earth may face similar challenges.

Disconnected from day and night, subjected to the extreme environments of space and the Martian surface.

What was it about the extreme environment of Antarctic winter that affected the ill-fated crew of the Belgica, and what can it teach us about surviving extreme environments beyond Earth without losing our sanity?

The Belgica set out on its journey from Belgium in August of 1897.

On board was the first international crew to make their way to Antarctica.

Previous expeditions to the poles were focused on national glory, but the Belgica was different.

This was a science mission, its crew composed of 18 men, one cat, and one lone American.

In command was an audacious 29-year-old Belgian named Adrien de Gerlache.

His first mate was 25-year-old Roald Amundsen, who would later go on to be the first person to reach the South Pole.

The expedition doctor was an American named Frederick Cook.

Cook was one of the few onboard with any previous polar experience, having spent a winter in the Arctic.

He was a keen observer of human nature, and Amundsen noted that Cook was "calm and practical at all times."

These attributes would prove critical later in the expedition.

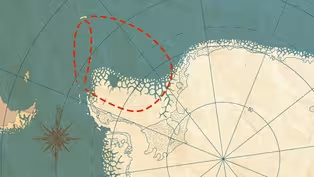

After departing Punta Arenas, Chile in December of 1897, the Belgica's plan was to make it to Antarctica, spend some time on the continent collecting scientific data for mapping and to study the ice, weather, and animal life.

And then a crew of four would remain there over winter while the rest sailed back to Australia for the season.

But Antarctica had other plans.

de Gerlache ordered the ship to sail farther and farther south, despite warnings from the crew that it was too late in the season to do so.

And in March of 1898, the Belgica became firmly stuck in sea ice, with the darkness of the long Antarctic night setting in.

South of the Antarctic Circle, the sun never rises above the horizon in the heart of winter thanks to the tilt of the Earth.

This brings about a time known as the "polar night," from around mid-May to late July.

The crew were ill-prepared for these conditions.

There wasn't enough winter clothing for everyone.

As temperatures dropped, food stores dwindled, and the sunlight disappeared, the crew slowly succumbed to malnutrition and mental disturbances.

Cook, the ship's doctor, wrote in his diaries that, "almost every member of the crew gradually became "afflicted with a strange and persistent melancholy."

- During the Belgica Expedition, one member of the crew became, it used to be called hysterical blindness.

A psychotic temporary blindness.

- [Narrator] Dr. Jack Stuster studies human performance in extreme environments.

- [Jack] Another became so paranoid that he would take his meals and find a little recess below decks and curl up in that.

And that prompted Frederick Cook, the only American on board and the ship's physician, to monitor the behavior of all the other crew members because everyone was slipping into a malaise, a depression brought upon by the monotony of their experiences.

- Researchers like Stuster think that in addition to vitamin deficiencies brought on by the lack of proper food, the perpetual darkness of polar night disrupted the crew's circadian rhythms in a way that severely impacted their mental health.

Our circadian rhythms are largely regulated by cycles of sunlight and darkness, and play a critical role in sleep, blood pressure, hormone levels, metabolism, and more.

- Cook knew that something was missing, and he thought maybe it was sunlight.

And so he would have the most seriously afflicted of the crew members stand naked in front of the ship's stove with just an overcoat over their shoulders to expose them to the light of the ship's fire, believing that that might have something to do with it.

He required the crew members to walk on the ice and those walks devolved into what became known as the madhouse promenade.

- [Narrator] The extreme conditions of life aboard the International Space Station also impact the circadian rhythms of astronauts, with documented negative effects.

Although not nearly as extreme as those on the Belgica.

The orbit of the station results in day-night cycles every 90 minutes rather than 24 hours, with astronauts witnessing up to 16 sunrises and sunsets a day.

Additionally, an astronaut's workload rarely fits neatly into a 9:00 to 5:00 schedule.

For example, the multi-hour job of docking a resupply craft is determined by orbital dynamics, not daily sleep schedules.

Over time, astronaut sleep schedules can be driven by the tasks at hand rather than the astronauts' own internal circadian clock.

This is risky.

Studies show disruptions to circadian rhythms can result in problems with focus, cognition, attention, and fatigue, and may have even played a role in the collision of a resupply capsule with the Russian space station Mir.

To mitigate these dangers, astronauts are prescribed medication to both help them sleep, and to help them stay awake.

But even with medication, research shows there's only so much we can fight against our programmed biological sleep cycle.

Former NASA Astronaut Dr. Cady Coleman flew on the Space Shuttle twice, and spent six months living aboard the International Space Station.

She also trained in Antarctica to prepare for her expedition to space.

- They're really putting an emphasis these days on testing those sleep medications and how much of them and what you feel like and understanding that really well before you launch.

They're finding that there was kind of a sort of older attitude that was like, "we're astronauts, we're just going to power through."

And I'm actually a chemist, so I say, "better living through chemistry," right?

But there's a lot of folks that are opposed to medications for various reasons or whatever, but understanding what they really do has been really helpful and what doses and when, and they've done studies to understand that people have woken up for an emergency, can still be alert while taking these medications.

And they actually test that.

- The Belgica mission is a useful analog for a mission to Mars.

The astronauts will also face a similarly endless night as these polar explorers did, outside the ship at least.

But inside, specially timed and designed artificial lighting can be used to better regulate circadian rhythms and match space sleep cycles to those on Earth, helping the crew to be happier, healthier, and more productive.

- [Cady] The presence of blue light inhibits melatonin production and that prevents people in a general way from being able to settle down and go to sleep.

So on the space station, they've actually got a lighting scheme where for about two hours before you go to bed, they've taken the blue light out of the lighting in the cabin.

You can still see everything, but it's without that effect.

And they've also got glasses that they wear that eliminates, like sunglasses that are eliminating only the blue light.

And this allows the crew to look at their computers and write notes to their family and things like that before they go to sleep, and also to go and look out the window.

The lighting seems to be actually really helping people settle down, go to bed, and then wake up in the morning refreshed and have day lighting.

- [Narrator] Once springtime came to Antarctica and sunlight returned, the mental health of the Belgica's crew began to improve.

Thanks to Cook's tireless efforts, only one crew member was lost due to poor health over the winter.

Cook is heavily credited with preventing the expedition from becoming a complete disaster.

But there was another team of polar explorers that fared much better than the Belgica's crew, despite ending up in a similar predicament: the Norwegian Polar Expedition led by Fridtjof Nansen.

He intentionally embedded his ship the Fram in Arctic sea ice in an attempt to drift his way to the North Pole in late September of 1893.

After a year and a half stuck, Nansen left the ship with one other crew member to try and reach the pole via dogsled.

The Fram managed to escape the ice after three years and made it back home.

Nansen and his companion, Frederick Johansen, however, were not onboard.

they were rescued by a British expedition after spending over a year alone together on the ice.

They fared quite differently than the Belgica crew, surviving their Arctic imprisonment in good health and spirits, reportedly without a single fight between them during their long isolation.

- And when they sailed into Christiana Harbor, Oslo Harbor now, they were greeted as if they had just returned from Mars.

- [Narrator] Nansen's leadership skills and meticulous preparation for his expedition are often cited as the key to its success in terms of crew health and morale, even though they never reached the North Pole.

Nansen read the journals of previous polar explorers to learn what to expect, custom designed his ship for the conditions, and made sure that he had all the appropriate supplies and crew.

On the other hand, the captain of the Belgica was ill-prepared for the conditions in terms of supplies and training, and his crew lost faith in him as a leader, vocally disagreeing with some of his decisions.

But one of the most unexpected key ingredients to the successful mission was actually the food.

- [Jack] Nansen's wisdom is arrange things sensibly and pay a special attention to the food.

Food is the quintessential habitability issue.

Everybody knows the importance of food when you're confined.

The airlines used to know this.

They don't so much anymore.

- The menu on the space station consists of about half meals ready to eat, much like the military would use, or even stuff that you might find in different grocery stores that's already mixed up and you just have to heat it up.

Meat on my particular crew was a very coveted item.

And we had three steaks that would last those nine days.

I would trade my steaks for borscht, which was Russian soup that I really loved.

And so there is some trading and in actually every crew, we share the food.

Food is incredibly important and you really can't underestimate the importance of it.

- For both the Belgica and the Fram, the crews were undoubtedly happy to be back with the rest of the world.

But after spending so long in an isolated, extreme environment, how do you adjust back to "normal" life?

- [Cady] Coming home is a different experience for everyone, but most of us have really made the space station our home.

We've been training around the world and spending a lot of time in different places without our families often, and you have to find a way to make yourself be okay.

When you get back home, I mean, for me, there was a lot of grief.

Partly just the work that we do up there.

I think it's so important and it takes a long time, even a month to get good at working up there.

And so by the time it's time to come home, you're just so, you're so good at it, you really just want to get more and more done, but it's time to come home.

- [Narrator] Despite the harsh conditions and toll they took on the physical and mental health of the Belgica crew, they did become the first expedition to winter over in Antarctica, and the first to camp on the continent.

Nearly 100 scientific publications came out of their work, including discovering new plant and animal species, studies of penguin behavior, and new insights on how the ice in Antarctica has changed over time.

And now, well over a century later, Cook's actions to keep the crew alive and sane are informing research on how to keep astronauts mentally healthy on the long journey to Mars.

Explorer Roald Amundsen perhaps put it best.

"The human factor is three quarters of any expedition."

What that means for us is, even if we create the most exquisite technology to get us to Mars, it will all be for nothing if a crew loses their minds along the way.

So understanding what humans need to be happy and healthy in space is just as, if not more critical, than the technology itself.

It's the seemingly little things we take for granted here on Earth, like food, sleep, and sunlight, that can make all the difference.

Uncharted Expeditions is a special series exploring the unique challenges facing human explorers as we set off in the next great era of discovery beyond Earth.

Make sure you subscribe to PBS Terra so that you don't miss a single episode.

And to learn more about the effects of isolation on astronauts in space, be sure to watch "Space: The Longest Goodbye" on the PBS app or just check the link down below.

Can Humans Get to Mars Without Going Insane?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 12m 32s | How can future astronauts best prepare themselves to face these challenges? (12m 32s)

Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | NASA psychologists prepare astronauts for the extreme isolation of a Mars mission. (30s)

Watch Space: The Longest Goodbye with PBS Passport

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | Get early access with PBS Passport. (30s)

What an Antarctic Disaster Can Teach Us About Getting to Mars

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 15m 9s | How do you keep humans sane and relatively content in isolation? (15m 9s)

Extended Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 1m | The grueling journey to Mars. (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: