The Taiwan Question

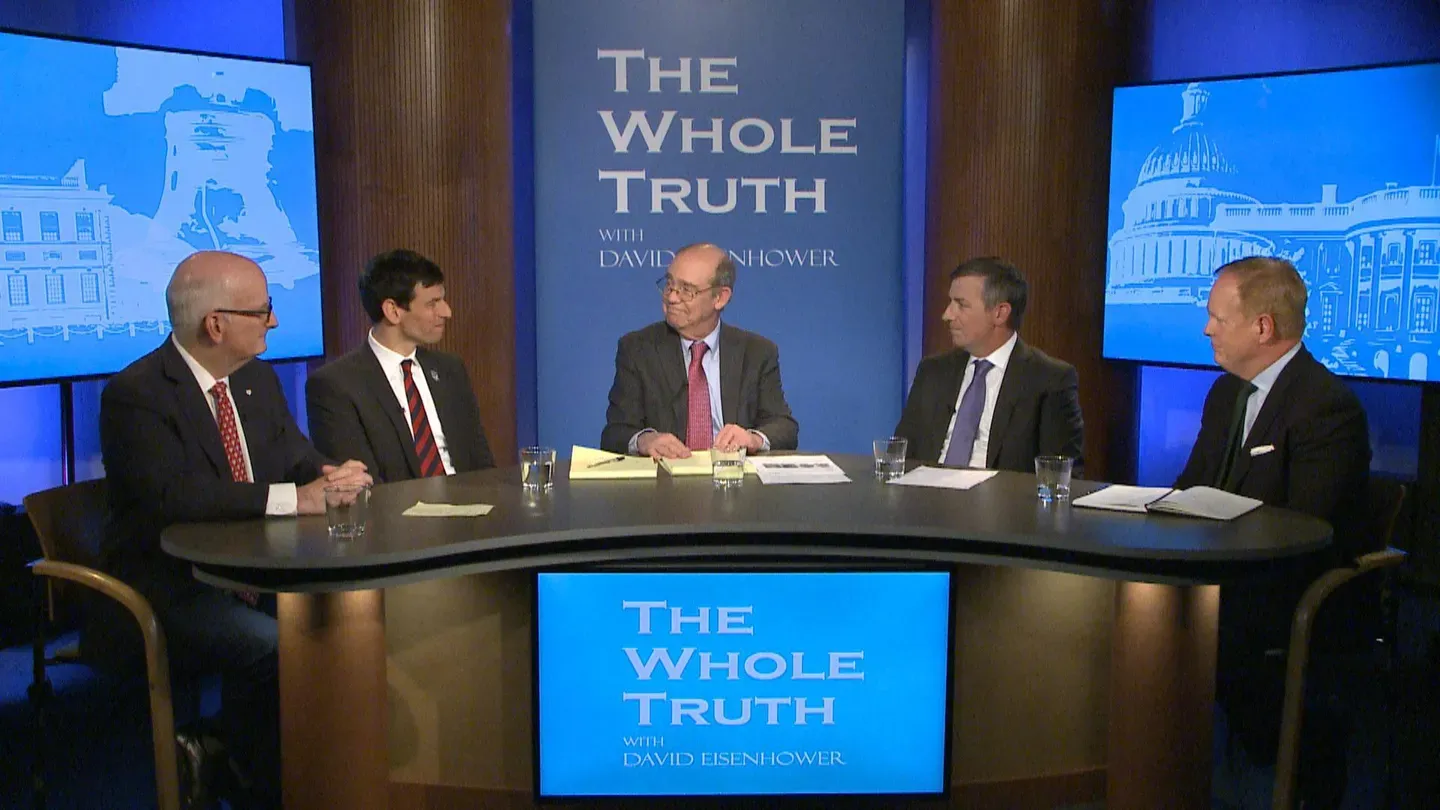

Season 7 Episode 701 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

American policy towards the potential flashpoint for world war with China.

Frequently called “the most dangerous place in the world,” many see the island of Taiwan as the 21st century equivalent of Berlin during the Cold War of an earlier era - the hottest of hot spots, the potential flashpoint for world war between superpowers - in our time those powers being the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America. What should be American policy towards Taiwan?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

The Whole Truth with David Eisenhower is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

The Taiwan Question

Season 7 Episode 701 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Frequently called “the most dangerous place in the world,” many see the island of Taiwan as the 21st century equivalent of Berlin during the Cold War of an earlier era - the hottest of hot spots, the potential flashpoint for world war between superpowers - in our time those powers being the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America. What should be American policy towards Taiwan?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Whole Truth with David Eisenhower

The Whole Truth with David Eisenhower is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipNarrator: Frequently called the most dangerous place in the world, many see the island of Taiwan as the 21st-century equivalent of Berlin during the Cold War of an earlier era-- the hottest of hot spots, the potential flashpoint for world war between two superpowers.

In our time, those powers being the People's Republic of China and the United States of America.

What should be American policy toward Taiwan?

♪ Announcer: This episode of "The Whole Truth" was made possible by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Education, William and Susan Doran, CNX Resources Corporation, and NJM Insurance.

Taiwan is a place of incredible dynamism, a vibrant democracy, a tolerant culture, and an economic juggernaut, with a role in the world's high-technology industries through its dominance in semiconductors, nearly equivalent to the role Saudi Arabia plays in oil markets.

But is it a country, its own country, or a breakaway province from China headed, one way or another, towards reunification with the mainland?

And what is the role of the United States, the proper role, the practical role on the question of Taiwan's future?

Joining me for this episode of "The Whole Truth" to discuss the vital question of Taiwan is Dr. Melanie Sisson, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Welcome.

Hi.

Nice to be here.

Thank you.

Yes, this is a very current topic.

We were talking before the beginning of the show, and I was reminiscing on a trip that my wife and I took to China years ago, over 40 years ago, and we took that that trip alone.

And I can recall a cold January day in Tiananmen Square.

We were in the Great Hall of the People and being shown the various rooms in that Hall, and one of them was the Taiwan room.

And I will never forget the expressions on the faces of our hosts and our feelings.

I think in that moment, I realized that Americans don't appreciate, perhaps, the importance of Taiwan to China, and I'm not sure that the Chinese appreciate the importance of Taiwan to the United States.

And so we have a kind of conundrum here, and I'd really appreciate your comments on this.

A number of interested parties in Taiwan-- the Taiwanese themselves, the Chinese, the Americans, and I suppose the Japanese-- uh...let's start with Taiwan.

You've studied this from a great power perspective, but from a local perspective, this has a bearing on it, The Taiwanese people themselves are Han Chinese, as I understand it, but they've--their views on their eventual course with China have changed, I believe, over the past number of years, and so forth.

What--how do you think opinion is on Taiwan itself?

Because of the different origins of some members of the population, as with any group of people, there's going to be differences in views and opinions sort of throughout the population.

And particularly, when it comes to an issue as important as reunification with China.

So, you know, they're, I think right now in terms of the public views, we can talk about views about specific reunification, of a specific type of reunification, of what the reaction might be depending on how China pursues reunification.

All of those are topics where there's a number of different views among the people of Taiwan.

Would you say that Hong Kong has passed through various gradations of reunification, for instance?

In other words, Hong Kong had an understanding, didn't they, in '97?

Yes.

And that has changed?

So--so, would Hong Kong be a sort of a laboratory, if we're discussing options here?

Well, I think that there is no question that the world, and in particular Taiwan, has watched very carefully what the experience of Hong Kong has been.

And I think, based on some of the recent polls that I've seen, the Taiwan people do not look favorably upon the one country, two systems approach and policy as it's been forwarded and effected by the Chinese government.

And I think it is reasonable to conclude that having seen that experience in Hong Kong has affected the views of the population of Taiwan on that matter.

Other interested parties-- could you elaborate on the Chinese interest in Taiwan?

In other words, I think we agree that perhaps Americans underestimate it to some extent.

But what is the--what is the validity of their claim, in your view?

And what is the intensity and reason for their insistence that there--there is but one China and Taiwan is part of that China?

The attachment to Taiwan on the part of China, as I mentioned before, comes very strongly, I think, from a sense of identity and history and a homeland affiliation of "There is but one China."

And that has been very consistent throughout over the decades, and it has not changed, and it is not changing.

The additional sort of imperative, I think, that China currently affiliates with Taiwan has to do with its strategic standing in its world and its ambitions regionally and potentially globally in terms of how it wishes to be regarded on the world stage by all of the other major powers and by the sort of community of states at large beyond the great powers.

China has an interest.

Taiwan...

I think a sort of ambiguous interest here.

What is our interest?

Oh, the United States' interest-- well, so, that depends on who you ask, frankly, but I think generally speaking, there are a number of ways in which the United States has thought about Taiwan and approached its relationship with Taiwan.

Since democratization, the nature and importance of that relationship has shifted for understandable reasons, and the United States is committed to supporting the democratic process in Taiwan and supporting Taiwan as a democracy.

The United States, obviously, has strategic interests in that region as well in East Asia, and we have longstanding, codified alliance structures-- Japan and South Korea, for example--that are very important that are legacies of the-- of the World War II era.

We take those very seriously, and we have a lot of presence in those places.

And there's no reason to think right now that we would change that.

What that has meant is that we have been able to exert our influence in East Asia in any number of ways and over any number of issue areas.

And generally speaking, the United States would like to continue to have that influence in that region.

Taiwan has sort of become a focal point for the U.S. interest in retaining that influence and China's interest in changing that balance over time.

China over time has developed in a remarkable fashion, at a remarkable pace.

Right.

Economically, it's become integrated with the global economy in ways that are profound and very thorough, and it also has grown in its military capability.

All of this sounds rather fluid.

So, in light of that, how would you assess China's options towards Taiwan, for instance?

Yeah, well, I mean, I think that the two primary options discussed about for China at this juncture are what might be termed the use of sort of coercion, efforts to convince the people of Taiwan that their lives would be better if they got along with China's preferred mode of operation and eventually to the extent that they thought it was in their best interests and for their well-being to unify with China.

So that can be done through sort of managing economic relationships, for example.

It can be done through the information sphere, sort of what information about China-- the population of Taiwan is exposed to, the nature of any of the sort of political level interactions that the two countries might have.

So, that's an approach.

The other one and the one that I think has, at least here in the United States, the Department of Defense with its ears sort of most upright, is the possibility of trying to force reunification through violent means, and that could be, you know, an overt invasion, or it could be something short of that.

It could be a blockade attempt, for example.

So, generally speaking, there's these sort of two approaches, the sort of "be patient and try to shape the conditions "around Taiwan such that the people ultimately decide that they prefer to unify," or eventually if that didn't produce the result that China wanted, then the option might remain for them to use force.

What--what--what do you think are the American range of options that are being discussed at Brookings and other places today?

Yeah, so, this actually gets a lot of attention right now, I think in part because of those dynamics that you've brought up and--and sort of this notion that maybe she has near-term ambitions.

The other element that's brought it to everyone's attention recently, I think, is advances in the Chinese military capability, and so this has been watched very carefully.

There are some who believe that as soon as China feels that it militarily is capable of taking the island forcibly, it will do so.

Our position has long been that China and Taiwan need to resolve the issue in ways other than war, without force, and we continue to--to hold that line very clearly, um...

But make no mistake about it.

That means Taiwan has a veto here.

Well, that's exactly right.

If--as Taiwan has become a democracy, what that means is that the Taiwan people are the audience here for being convinced to reunify.

Right?

Right, right.

It cannot be a government-to- government decision.

That's not how democracies work.

Right, And so, that's right.

The sort of weight of that is the Taiwan people.

The other options for the United States are communicating to China that were they to act forcibly against the island, they would suffer a very high price for doing so, and that price can be brought by-- in the defense of Taiwan by the Taiwan people and the Taiwan military, that the United States does engage with very deeply in terms of training, assisting, and arming.

It can be done now economically, given the state of integration of China with the global economy.

It can be done diplomatically.

I've heard a lot of assessments of American forces in the Far East, and very pessimistic ones, about the state of our naval readiness in that region and the state of our Asian fleet, and so forth.

What do we have to do?

A lot.

So, I don't think it's so much of a readiness issue with our forces today.

I think there's a combination of factors.

I mean, the primary one being that China's capabilities have changed, and there's just no getting around that.

The other thing there's no getting around is the tyranny of geography and time, is that you may have noticed that Taiwan is an awful lot closer to mainland China than it is to mainland United States.

Oh, yeah, oh, yeah.

Something a little short of 7,000 miles.

Yeah, England is much closer to Germany than it is to the United States as well.

I mean, we have far-flung offshore interests.

Now, you mentioned you're associating this with China's rise to great power status, and I'm curious.

One of the arguments I think here is that if the United States simply washes its hands of Taiwan-- it's beyond our reach, we gave them to understand that it would be returned at one time, we have signed them away in The Shanghai Communique acknowledging One China and so forth, were we to do that, that would greatly threaten the sort of international norms-based system of law and understanding, and so forth.

We would invite aggression.

Uh, I'm wondering if that is an accurate assumption in a way.

China's emerging as an actor on the international stage.

Would you call them a satisfied power?

Would you call them an insurgent?

Are they a responsible partner in global order, or are they a problem?

I would say yes-- Yes.

to all of that.

I mean, I think that-- I think that what China is is behaving as a normal, great power-- a normal rising power would, which is to say that, no, it is not satisfied with the entirety of the structure of the international order today.

No surprise.

That order was designed primarily by the United States in the aftermath of World War II, and it was designed in a way that prioritizes and privileges U.S. interests over the interests of all other states in the system.

And this is--this is what China sees-- That's their argument.

That is their argument.

We did include them in the UN Security Council.

We sponsored--yeah.

Certainly, and yet there are ways in which they would like to see changes made to how the international order works and operates.

And so, they are pursuing those changes as they rise in the ways that they can.

Right.

Sometimes, that is through overtly international legal measures.

Right?

Using those legal mechanisms to press their claims and make their cases, sometimes it's looking for loopholes in the international legal order-- Well, working any way with the international order is in a sense reaffirming it.

It is at least acknowledging it as the reference category, if you will.

Right?

Right.

Now, I think if you-- if you ask, "What is it that China wants at the end?

What is the world order that they would like to see?"

You know, I think the shorthand for that would be that their interests are privileged generally in the operations of the system and the structure.

They have a very sort of ordered sense of how things should operate, where China's interests are privileged at the top.

Now, that doesn't mean it would be complete subjugation of other countries and other peoples, but it would be still that the idea of sort of the global apparatus would-- would serve Chinese interests more rather than less.

Mm-hmm.

China is--has it achieved parity yet?

In other words, are we in a bipolar-- I don't think so.

international system?

We're still a unipolar system of sorts, or what?

I think of sorts.

I think that we should all remember the Unipolar Moment is not, um... is--is historically very rare.

Right?

Right.

And this is not something--you know, we have all-- we--I think the United States and I think largely many portions of the world have benefited from a unipolar moment.

That's shifting.

I don't think it's gone entirely.

I don't think we're in an era of bipolarity or multipolarity.

I think that's part of what's being contested right now-- Mm-hmm.

is to what extent the international order and U.S. interests will start to accommodate the interests of China or accommodate the interests of Russia-- And that requires a psychological shift in a sense in the United States, right?

Because when the polar order did come about, I think that we had a lot of thinkers that believed that that was inexorable, the end of history, resulting in the-- in the triumph of certain principles, and the United States has sort of been in the center of that.

Even though the Cold War bipolar structure had gone, it didn't mean that there weren't going to be these contestations about the way people wanted to live in the world.

Right.

Actually, that's a philosophical question I can pose to you.

Would you characterize the Chinese outlook as any way more global or more Chinese as they get more powerful?

I think, from what I have seen, I think there is a deep and profound sort of Chinese identity, and that I think that that's one of the tensions that China increasingly will have to deal with.

And you've seen them constrain the information space so that the population, the government, you know, encloses the population and sort of deflects information and inputs, that it would prefer the population not to have through these modern modes of technology.

And so I think they are well aware of the potential effects of that form of globalization, of globalized thinking on the Chinese population.

And it seems to me that they're not quite ready or confident-- Confident?

in the sort of center of Chinese identity-- Which is interesting.

Which means they're not confident in their own people, in a strange sort of way, to see the world as Chinese, as they see it.

I think--I think that there is a worry.

I think it does reflect a worry that the centered Chinese identity could be vulnerable or distorted.

I think they would probably see it as, you know, being intentionally contaminated by other forces, as opposed to sort of anything inherently about the Chinese people.

A phrase for its some years ago was "cultural pollution," I think.

Oh, is that what it was?

Yeah!

I mean, they have, what, uh... Xi is now the fifth-generation leader.

I think he's the subject of the third general resolution of the Communist-- Communist Party.

We heard talk of that when we were in China-- the third generation, the fourth generation.

We haven't been back in a while, but, uh... how do you assess Xi and Xi thought in the direction of the-- of the Chinese world?

Um...what I've seen in terms of their strategic writings and what it is that they want to see in the world is that, uh, there's an opposition to sort of what they might call chaos, and there's a strong preference for structure.

There's a strong preference for sort of clean lines, if you will.

They have taken, you know, some very clear and consistent stances, for example, certainly on the Taiwan issue, which we discussed before, but in other areas as well.

And--and I would expect that to continue.

There is, for example, in a lot of the strategic writing from China, Xi and otherwise, about the inviolability of sovereignty.

And they mean that not just in terms of territorial aggression, but in terms of, you know, your business in your country is your business.

My business in my country is my business.

We operate things as we see fit.

You operate things as you see fit.

And the way to retain peace in the international system is to respect sovereignty in that way, which is why you see them bristle very much at conversations about human rights and certainly human rights violations in China itself, and the sort of deflect-- the deflection that they have for that is, "This is a matter of sovereign interest, and you're trying--" So, now, generally an ambition essentially to, uh... what would be the term-- Sino-phy or whatever-- Chine--export a faith.

In other words, their--their notion of sovereignty is something that sounds quite compatible with international order in many ways.

In other words, they're gonna respect the vital interests of other nations, their sovereignty.

Correct?

Well, so, that is an interpretation, to be sure.

I think it is--it is-- if you take them at the word of respecting sovereignty in that way, then it's--then you would not interpret their behavior in the international system as trying to promote a Chinese ideology or to supplant a Chinese form of politics in other countries.

It's not the Soviet Union, right?

Right.

It's not that kind of expansionist ideology, if you will.

Taiwan would involve a question of sovereignty, but that would be it.

In other words, if Taiwan can be resolved on the basis, a satisfactory basis in which the Chinese feel that their sovereignty has been respected, we do not necessarily see it as a consequence of that, what we used to call the Domino Theory in the Cold War, where--where you would see a sort of an expanding China over the map or an effort to sort of drive some sort of ideological victory.

Yeah, well, two things on that is I would say is first, China has been very clear that Tai--there is but One China.

And what the U.S. position has been is to acknowledge that as China's view, not to acknowledge that there is-- We didn't acknowledge that in Shanghai?

The--the communique is-- the language is very sort of intentionally precise about this is to say we acknowledge that China's position is that there is but One China.

Right.

So that was intentional and very careful.

I see.

The diplomacy around Taiwan, starting from that moment, has been, you know, excruciatingly precise for that very reason, because the words really matter.

Mm-hmm.

Oh, they do.

And it has continued.

Right.

In terms of the-- so what it would mean-- so China certainly would not see a return-- they would not see reunification-- unification/reunification with China, as any change in the sovereign status, because they believe there is but One China, and-- Sort of without notice, so to speak.

This would not be the fall of Berlin or--or some Marxist revolution in Latin America.

This would not be necessarily an ideological challenge, but it sounds to me that there's a basis for resolution here.

Well, there are some who, regardless of the extent of the ideological expansionism, do see Taiwan as sort of the first in what might be considered a Domino situation insofar as they see it as very important to China's being able to exert its influence throughout East Asia more broadly.

So, that's a strategic argument, not so much an ideological one, which is that China would like to control the waters of East Asia and it would like to control the economic exchanges regionally.

Right.

It would like to be the dominant power.

Right.

So, the Domino Theory here-- Where they're in fact dominant.

Where they are physically dominant.

Where they are physically dominant.

So, it's not an ideological dominant theory so much as it is-- Which distinguishes this whole situation from Cold Wars, far as I can see.

I agree.

Yeah, the U.S.-USSR split was really within the framework of sort of Western ideas.

Marx was a Western philosopher and so forth, so they're competing for the same audience, so to speak, and the Chinese and Americans perhaps different.

As time winds down here, I'd like your projection on two fronts: first, areas of potential agreement between China and the United States over the years.

If we're gonna have an international order, if we're gonna share it with the Chinese, we must come together on norms.

And second, your prediction flat for Taiwan.

Where are we gonna be in 20 years?

A system requires a certain consensus, strategic consensus, a political consensus.

Do you see areas where we just implicitly agree?

So, I don't know that I would say implicitly is the word that I would apply, but I think there are very clear areas where there are aligning interests that China and the United States can have, and I hope we'll continue to work together.

Those primarily today, I think, are climate change and things like pandemic responses, which, you know, is front of mind, again, unfortunately.

But those are certainly two areas, and international, economic sort of rules of the road.

Mm-hmm.

Both countries have gained enormously from China's accession into the WTO.

Both countries, I believe, would like to see economic growth and development continue, and so there is going to have to continue to be a way and shape in which these two countries can accommodate each other's interests in that arena as well.

And Taiwan as a potential obstacle to better relations.

Where is this gonna be?

In 20 years?

I'll tell you honestly.

I--my hope is that it will look very much like it does today at worst, and at best what my hope is, is that the democracy in Taiwan continues to flourish and improve and that it becomes able to negotiate with China a way of resolving the issue peaceably that both sides can live with.

But if we can't get to that, then my hope is that it will just stay frozen and do this-- this dance for indefinitely.

Been doing it for a long time.

We've been doing it for a long time, and it is far preferable, frankly, to some of the alternatives.

Ha ha!

Far preferable.

Well, it's a fascinating and unending subject, and it's been a real pleasure, privilege to have you.

Oh, this was a delight.

Thank you for such excellent conversation.

I really appreciate it.

Wonderful.

Appreciate it.

Thank you very much.

For some, protecting Taiwan from being placed under the control of the People's Republic of China by force is the ultimate test for American foreign and defense policy in the first half of the 21st century, the consequences of which will largely determine America's role in the world for the remainder of the century.

Others believe it is neither feasible nor desirable for the United States to defend Taiwan should the People's Republic of China seek to conquer it by force and that there can be no harm to U.S. credibility if we do not make commitments that do not exceed our capabilities.

What does the world look like if the United States were to fight to protect Taiwan?

What does it look like if we decide this wouldn't and shouldn't be our fight?

As always, we leave it to you to decide for yourselves the whole truth.

I'm David Eisenhower.

Thanks for watching.

♪ Announcer: This episode of "The Whole Truth" was made possible by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Education, William and Susan Doran, CNX Resources Corporation, and NJM insurance.

♪

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

The Whole Truth with David Eisenhower is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television