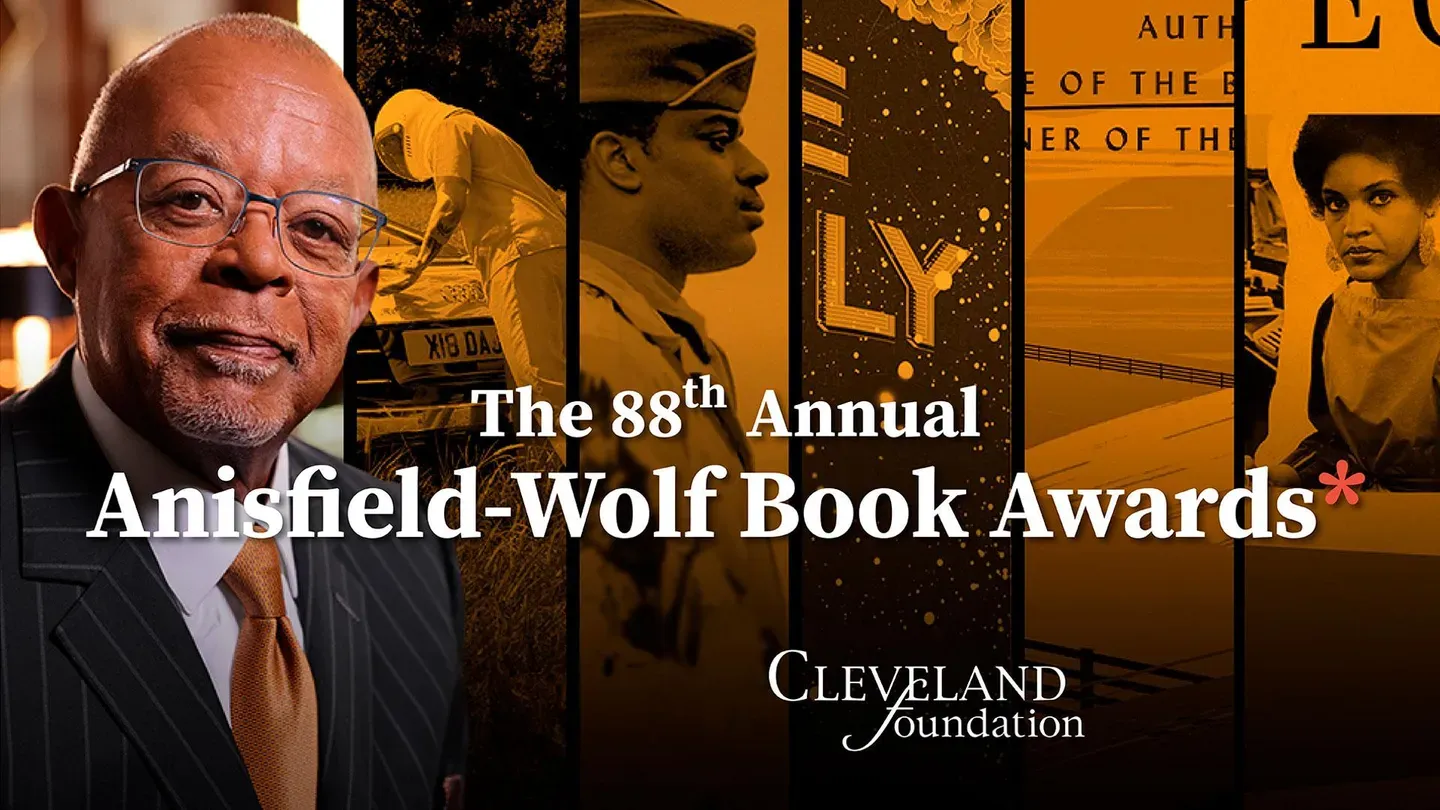

The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

A documentary hosed by Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. about the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards.

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. hosts a documentary about the 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is the only national juried prize recognizing literature that has made important contributions to our understanding of racism and human diversity.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television

The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. hosts a documentary about the 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. The Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is the only national juried prize recognizing literature that has made important contributions to our understanding of racism and human diversity.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

-Funding of the Ideastream Public Media production of "The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards" was provided by the Cleveland Foundation.

♪♪ -The average American reads about a dozen books each year, millions and millions of words arrayed across countless pages.

These books can be so many different things to so many different people.

Entertainment.

Escape.

Enlightenment.

But we know that books can be much more than that.

Books can be our protection.

Books protect our histories.

They protect our perspectives.

And they protect our narratives, especially the ones so often ignored or erased.

♪♪ That's why it's so important that we honor and celebrate the brave novelists, scholars, and poets who fearlessly tell all of our stories and give them the protection they deserve in the fight against bigotry and ignorance.

These books become our sword and our shield, our armor.

♪♪ Hello and welcome to the 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards.

I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr., and it's been an honor to spend the last 27 years as the chair of the jury for this historic book prize.

The Anisfield-Wolf Book Award was created in 1935 by the Cleveland, Ohio, native Edith Anisfield-Wolf, a poet, to honor and celebrate authors who dedicate their craft to combating bigotry, celebrating diversity, and demanding equality.

It is the only American book prize of its kind.

Stories like those these authors tell often have been neglected, overlooked, silenced, even censored.

In this program, we honor this year's winners of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards, authors who have given us all a new suit of armor with their words and ideas.

[ Cheers and applause ] We begin with a collection of poems that express the internal conflict felt by a queer Black man, a feeling of being simultaneously celebrated but also tortured.

This year's winner for Poetry, Saeed Jones, pays homage to several Black icons -- comedians, musicians, artists, recognizable names and legends who had recognition stolen from them.

Growing up in the American South and then honing his craft in New York, Jones wrote "Alive at the End of the World" while living in Columbus, Ohio.

Through his poetry, Jones describes facing personal grief while, in his words, "running for your life."

-Part of it is there's humility.

We are alive at the end of the world, and that is something to be grateful for.

We are here.

We have lost.

I have lost so many people.

I am here.

I owe it to them to stand in my humility and gratitude and make the most of what I can while I am here.

However, girl, it's a mess out here!

[ Laughs ] ♪♪ I kind of think of, like, laugh to keep from crying a bit in the book and in the title.

Like, "Alive... at the End of the World."

Well, great!

You know what I mean?

This is the -- This is the era that I've been chosen to deal with?

Wonderful.

Yeah.

[ Chuckles ] The collection was my attempt to capture, from my perspective, what it feels like to, on one hand, be doing the -- the reckoning of -- of personal griefs and histories, you know, kind of often contained in your own body.

You know, just try to make sense of your own history... while kind of running for your life, right?

It's just hard enough to deal with, let's say, your personal grief or heartbreak.

But in addition to all of that, you know, whether it's state violence, climate change, white supremacy, white nationalist violence, violence against queer people, all of that's happening at the same time.

I just wanted to capture all of that because you don't get to choose.

Like, you can't stop grieving, right?

We can't -- It's not an on-and-off switch.

But also we can't turn society on and off and say, "I need a moment to process my personal feelings.

Can white supremacy, like, give me a day off, please?"

-Because Black people don't usually mountain climb.

-They don't?

-And -- We sing about it.

-They sing about mountain climbing?

-Ain't no mountain high enough.

You've heard the song.

[ Laughter ] -I was fascinated that I had a much stronger response to his passing than I thought.

I didn't know Paul Mooney.

I never got to see him do stand-up.

You know, I liked and respected him, but he wasn't someone that I was, like, mentioning every day by any means.

And I was like, "Okay.

That's interesting.

Well, let's work with this."

The book kind of has a spine in which I kind of create my own Black cultural canon and say, "Here are my geniuses."

♪♪ -♪ A few stolen moments is all... ♪ -Each poem in the book is inspired by and about an aspect of each of those people's lives that I did not know about.

And I am turning toward these Black artists, which is also something this country loves to do.

This country loves to -- You know, I'm using quotes here.

Like, worship Black artists while also kind of stealing from them.

So what does that mean?

I know I have a different relationship.

I hope I -- I certainly don't think I have a predatory relationship to Black art, right?

But our country does.

-♪ Boy, you don't know what you do to me ♪ ♪ Tutti frutti, oh, rootie ♪ ♪ Tutti frutti, oh, rootie, eee ♪ ♪ Tutti frutti, oh, rootie ♪ ♪ Tutti frutti, oh, rootie, tutti frutti ♪ -Little Richard, I think, is a really important and painful test case for conversation about appropriation because Pat Boone, one of Little Richard's contemporaries -- So it's not like this was done years after Little Richard recorded "Tutti Frutti."

It was, like, within, you know -- It was pretty, you know, simultaneous.

Pat Boone, a white artist, covers the song but also, like, waters down the lyrics, right?

So it's also like -- you're not just taking Little Richard's song and artistry, you're also diluting it in a disrespectful way.

Pat Boone made millions and millions and millions of dollars off of his stolen version of "Tutti Frutti."

And Little Richard just was basically kind of getting dimes and was understandably angry about it for the rest of his life.

For decades, he would talk about it, you know, whether someone brought it up in an interview or not.

"Ain't that what you really want?

A stadium full of white people screaming your stage name and a smashed guitar where your... [Notes run on piano] ...used to be?

Ain't that what you deserve?

God is the only reason I haven't already held you down and spat the hook into your mouth like a poison that will kill us both.

It's that Pat Boone watered down and added bleach to 'Tutti Frutti,' and it was a bigger hit than Little Richard's original version.

It's that when Little Richard said, 'If Elvis is the king of rock 'n' roll, I'm the queen," he wasn't being cute or sassy.

He was correcting the historical record and demanding equity that he never received.

In America, one way to suffer a death before you die is for people to applaud you even as they steal from you."

There's a statement on gender there, but he's also saying, "I should be held at the same level.

If we're going to create a hierarchy, don't put Elvis above me and the many other Black artists, by the way, that Elvis stole from.

Like, at best, he's my peer, but frankly, he's my protégé because he's stealing from me."

You know what I mean?

And -- But I think because Little Richard was Black and queer and presented in a certain way, his outrage often was not taken seriously or, even worse, it was regarded as entertainment.

People acted like he was a clown.

♪♪ ♪♪ One of the many ways to die a death in America before dying is to have people applaud for you as they're stealing from you, and that's what cultural appropriation really is about, you know?

It's like that, "Oh, thank you so much.

I love you!

Oh, you're a god!

You're a diva!

You're an icon!

But I'm also mining you.

I'm draining you of everything I can extract."

And white supremacy thinks it's slick.

It really thinks it's slick.

It thinks if it smiles and uses nice words and bright eyes and everything and perfume that the violence is not violence.

But we know.

Those of us who are on the end of that spear or that knife, we know exactly what's going on.

There's a direct relationship between cultural appropriation and capitalism, which is to say capitalism in the western world doesn't exist without enslavement.

The original appropriation.

Now when artists, I hope, speak up about things like cultural appropriation, people aren't laughing anymore in the way they laughed at Little Richard.

And I think we owe it to him.

It's a debt he had to pay that he shouldn't have had to.

-♪ A-wop bop a loo bop, a lop bam boo ♪ [ Cheers and applause ] -My mom raised me as a single parent.

She was a pretty great mom.

She was very funny.

She was so important to me and still is.

And I think 10 years into grieving her, there will always be questions that I wish I could take to my mother and talk to her about.

But at some point, when you've lost a parent, you begin to acknowledge, "Oh, okay.

I'm just gonna have to figure this out on my own?

Okay.

Yeah."

-♪ I'm saving all my love ♪ ♪ Yeah, I'm saving all my lovin' ♪ -Every once in a while, I will -- I don't know if you've had this experience, but, like, as you start growing, you, like, begin to, like, hear your parents' laughter in your laughter.

And there have been some times where I've laughed and I'm like, "Aah!"

You know?

[ Laughs ] Um, and, you know -- And it's always a little, like, ghostly, but very funny.

I liked the idea in this book where I have this pantheon of Black icons.

Why shouldn't my mother just be standing there right alongside them, you know?

She's -- She's one of my legends.

♪♪ -Our next award-winning author also invites the reader to wrestle with misunderstanding and prejudice, illuminating the unique, sometimes lonely, and often stereotyped experience of Asian Americans in the Midwest.

One of two Fiction award winners this year, Lan Samantha Chang grew up in Wisconsin and now serves as the director of the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop, one of the most prestigious graduate-level English programs in the United States.

Her novel "The Family Chao" is a murder mystery that explores a family whose members are as unique and individual as the delicacies served at the restaurant they own, yet it's that complex individuality that gets lost on their small-town Wisconsin neighbors.

♪♪ -Womp-womp-womp.

Oh, yeah.

I love working with writers.

For me, as a Midwestern native, it feels exciting to know that so many of our country and the world's great writers have come through this town.

Knowing that "Chao" was also "chaos" in plural, it was not the reason I named them Chao.

They always felt like they were The Family Chao.

Oh, yeah, I'm sure my subconscious was working on it.

They are an extraordinarily chaotic bunch.

♪♪ One of the things that was interesting to me about growing up in a family of four same-sex siblings -- I have three sisters -- was the way that each of us was so extremely different.

And I think I had that in mind when I wrote about the Chao brothers.

Part of the reason that I wanted these brothers to exhibit their personalities as fully as they do in the novel is because I want to make it clear that Asian Americans are not to be viewed as kind of a monolithic, quiet, studious, you know, hardworking model-minority culture that I think is sometimes represented in books and films.

I wanted them to be themselves, individuals, unique, reacting to their circumstances, reacting to the oppression in which they've grown up in completely different ways.

[ Indistinct conversations ] ♪♪ I was writing for my own entertainment for large parts of this novel, especially around food because I'm a big food eater and I'm also fascinated by what I consider to be the exotic food of Middle America.

So, I grew up in a family where we ate Chinese food every day because my father wasn't happy unless he had rice and meat and, you know, Chinese food.

And I was growing up in a capsule of Chinese and surrounded by a community in which people were eating food that I never, ever had at home.

We really did not eat raw vegetables in the way that a lot of my classmates did.

So something like ants on a log, which, for those of you who don't know, is, like, celery filled with peanut butter and dotted with raisins, is just completely delightful and absurd to me.

And, of course, I had to include it in the book.

"James asks for her order.

Tea.

Spicy tofu.

Does she want it with or without pork?

She wants the pork.

Would she like brown rice?

No, she says, brown rice is an affectation of Dagou's, not authentic.

White rice is fine.

Whatever her complications, James thinks, they're played out in the real world, not in her palate.

But Catherine's appetite for Chinese food is hard won.

She's learned to love it, after an initial aversion, followed by disinclination and finally exploration.

Everyone knows she grew up in Sioux City eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, carrot sticks, and 'ants on a log.'

Baking, with her mother, Margaret Corcoran.

Yet, her immersion in these skills taught to her by her devoted mother, have, over time, created a hunger for another culture.

James can see it in the focused way she examines the shabby restaurant.

He can see it in the way she looks at him.

It's a clinical look, a look of data collection, but also of loss.

Why doesn't she do her research in China, where her biological mother lived and died?

Because she worked so hard at her demanding job in Chicago.

In the meantime, the Fine Chao will have to do."

One of the interesting things that I discovered while I was writing this book is that people's feelings about their Chinese-American-ness and their Chinese-ness can be seen in how they relate to and adapt to the food around them, including Chinese food and American food.

Their experience could be easily had by many.

[ Clicking ] ♪♪ -My name is Shaan Dela Cruz, and I love cooking.

As Filipinos, that's how we connect.

You know?

Mostly we connect with food.

If -- As a non-Filipino, if you go to a Filipino house, first thing they would ask you, "Have you eaten yet?"

That's how we show generosity and hospitality.

Filipino breakfast.

If your grandma was still here, it's just the fact that -- that's what she's used to.

That's what the family is used to.

So if we ourselves disconnected away from that generation, we don't want to lose that.

We don't want to lose that -- that tradition.

So I have her eat as much Filipino food as we can.

We try our best for her to know that this is us.

This is us as Filipinos.

She'd actually watch me cook sometimes and, you know, ask questions.

So her to learn all these traditions that we have through food is -- it's gonna be great.

And hopefully -- cross my fingers -- throughout the years that she grows up, you know, she's still gonna have it in her.

-I wanted the book to contain the largeness of, like, many cultures.

And one way to show that is by including the food.

♪♪ The problems that the family are having become very much available, wide open to the public.

The second half of the book is about the representation of the family conflict in the world at large -- in the white community, in the media, on social media, and then ultimately in the courtroom.

I wanted to show how that internal drama could be seen entirely differently, could be distorted, re-envisioned to serve the stor-- the purpose of other people's stories about how they thought Asian Americans should be or could be.

There was so much that could be done with the gaze of the outsiders, the outside gaze upon this Asian American community and particularly this family that I hadn't envisioned when I started the book.

The entire second half of the book became about that vision, that gaze.

♪♪ -Hey, hey, ho, ho!

Racism has got to go!

Hey, hey... [ Indistinct shouting ] ♪♪ -My writing included the year of 2020.

I was finishing up the book around then, and in 2020, there -- there came with the pandemic an increase of violence against Asian Americans and Asians.

♪♪ This may be hard to believe, but the increase in violence did not affect the book because in my vision of the book, I had always known that the potential or the actuality of that kind of violence existed.

♪♪ [ Birds chirping ] I am on the campus of Kenyon College for the Kenyon Review Writers Workshops, and I am one of the fiction faculty for the summer.

-Do you think a story explores a world or just a person?

-Some stories explore the world.

I grew up in a family of immigrants in the Midwest in a situation in which we were all quite isolated, culturally and personally, from the town in which we lived.

And...when I first started writing, I was writing with this sense of desperation that no one would ever be interested in our story or a story of a family like my family and that, by extension, we would be -- our story would be erased, eliminated, when we left the Earth, that there was no literature that would tell, you know, a story describing what we had been through.

Part of what I like about being a teacher is that I feel that I'm helping people get the tools to tell their stories.

♪♪ -Taking ownership of a forgotten storyline is also an intention of this year's Nonfiction Award winner.

America's fight against fascism in World War II was widely celebrated and honored, but what was mostly forgotten was the involvement of Black Americans in the war.

Matthew F. Delmont is a Dartmouth College historian.

He teaches readers about what was dubbed the Double V campaign, in which Black Americans fought to win two wars in the 1940s -- one against fascism abroad, the other against racism at home.

"Half American" not only shows us that Black Americans were heavily involved in World War II through combat and supply.

It also uncovers the fact that Black Americans were vital to our victory.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Listen.

I've leaned fully into the role.

[ Sizzling ] Hardcore suburban dad.

It fits me.

They think it's cool that their dad published a book, and the book is dedicated to them, which was fun for me to be able to do.

What I hope my kids take from the book is that this is part of our shared history, both -- by which I mean our family's history, but also our country's history.

One of the things my students ask me in the classroom all the time is, why would Black Americans choose to fight for the United States during World War II, given all the racism, given the violence, given the lynchings that were taking place.

And it was an active debate going on in the start of the war whether Black people should choose to fight this war because they recognized the hypocrisy.

They recognized that the United States was claiming to fight this war for freedom and democracy, while still having a segregated army, while still condoning this kind of Jim Crow segregation and racism all across the country.

"To make matters worse, German POWs now joined white American troops in the whites-only section of the mess hall.

Fort Lawton was hardly an exception.

Across the country, and especially in the South, where the majority of Nazi prisoners were held, Black troops reported that these Germans were allowed to ride buses and trains, use latrines, and eat in the cafeteria alongside white Americans.

In a war full of humiliations, this treatment was particularly outrageous.

White soldiers and civilians treated Nazis, who only weeks earlier had been fighting against the Allies and trying to kill Americans, with more respect than Black troops who served their country.

Seeing white Americans being so friendly with German POWs was perhaps the clearest evidence that Jim Crow segregation and the Nazis' master race theory were two sides of the same coin."

Black people understood really clearly that Nazism was a threat not just to Germany, not just to Jewish people, but really to the entire world.

This theory of Aryan supremacy, this theory of white supremacy, was something they recognized very clearly because they saw that Hitler was explicitly drawing on American racial policies to help justify his treatment of Jews in Europe.

They saw where this was going to lead.

The other reason Black Americans choose to fight, though, is because, by and large, they're deeply patriotic.

They want to do their part to help win the war.

They want to fight for their country.

♪♪ I want people to remember that patriotism and dissent can be intertwined.

I think one of the unfortunate parts about our political dynamic today is that there's a sense that you either are deeply patriotic and you can only love the country and never criticize it or that you can only dissent and you can't find aspects of the country that you care about.

That's never been true for Black Americans.

I think the history of World War II makes it evident.

Black Americans are fighting not for what America is today, but what it can be in the future.

And that's why I think the story is so powerful from the Black perspective because World War II wasn't just those years of '41 to '45, but it was a much larger and longer question about, what kind of country are we going to be?

Are we going to be the kind of country that condones lynching and condones Jim Crow segregation?

Are we going to be the kind of country that all people can actually have the opportunity to live successful, fulfilling lives?

It's not just saying, oh, yes, Black people happened to be in World War II, but these people were really good at their jobs, whether that was being a pilot, whether it was being a truck driver, whether it was being a Marine, whether it was being a tank battalion member.

These Black Americans were extraordinarily skilled.

They epitomized Black excellence.

I want to make sure people understand that.

They were at the top of their game.

♪♪ They didn't pay attention to what Black Americans could bring to the war effort.

They turned away Black people with PhDs from Harvard, with advanced language skills, with technical abilities.

They only focused on what people's race was.

America couldn't have won World War II without the contribution of these Black troops.

The second key thing the book tries to do is talk about the Double Victory campaign, which was really the rallying cry for Black Americans during the war because they saw themselves as fighting two wars at the same time.

The Double Victory campaign gets started based on a letter by a man named James G. Thompson.

And in December of 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he writes a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, which was the largest and most influential Black newspaper in the country.

Thompson's letter asks, in part, "Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?

Is the America I know worth defending?"

The Courier, in part, then takes Thompson's letter and uses it to launch the Double Victory campaign.

The Double Victory campaign was a call for Black Americans to fight for victory over fascism abroad but also victory over racism at home.

And those aims were intertwined throughout the war years because Black Americans understood it wasn't enough to defeat the Nazis militarily if you came home to racism and white supremacy in the United States.

♪♪ ♪♪ One of the challenging things in telling the story of Black contributions to World War II is that the story was really written out of the history books in the years after the war.

The story was well-known by Black Americans during the war.

It shows up in the Black press.

Black veterans obviously knew their stories.

They told it to their families.

But when those first histories of the war get written, you don't see a lot about Black troops.

They tend to focus only on the combat troops, which by and large were white troops.

That was a concern.

It was offensive to Black veterans who understood the important role that they played and saw those early histories really as an attempt to whitewash the history of World War II, really an attempt to leave them out of the story.

And I think, as a result, Black veterans just didn't get the same kind of warm reception that white veterans did in the years after the war.

Unfortunately, for too many white Americans, they wanted to return to the status quo.

They wanted to come back to the same kind of racial hierarchies that they had left behind.

And we like to think that World War II was one of the rare moments of real national unity, but the reality is, when we get into the evidence, it just was not.

There was fraught, fraught racial tensions throughout the war.

♪♪ -I am Robert P. Madison.

And on September the 1st, 1944, we went into battle.

Absolutely a Buffalo Soldier.

92nd Infantry Division.

When I came back in my uniform, no parades, no nothing.

That was it.

So there was not a recognition of what contributions had been made by Black soldiers.

Not only soldiers.

Sailors.

The entire effort to defeat Germany and the Axis during the Second World War.

Soldiers who were African-Americans were determined to demonstrate how heroic they were, how responsive they were to the cause of America, that they were trying to prove something.

We were trying to prove it.

And beyond -- beyond the whole effort of defeating the Nazis and all that, we wanted to demonstrate that we could fight just as much as anybody else, suffer just as much as anybody else, and die like anybody else.

It was a mission.

-I wrote "Half American" for men and women like Robert Madison.

[ Cheers and applause ] The tradition has been the people in power tend to get to determine what kind of narratives get told about the past and what kind of histories get foregrounded.

I think we're at a moment where there are more historians, both within the academy and popular historians, who are able to tell different kinds of stories.

A lot of those are being welcomed by readers, but a lot of them are also being attacked by different parties who are concerned about this way of re-understanding our nation's history.

These are stories of Black veterans, Black defense workers, Black citizens who were civil-rights activists who fought for America, either militarily or fought as civil-rights activists, to try to send the country in a different and better direction.

And so the question I would ask people who want to not teach these histories is, what are we trying to exclude?

Do we really not want to have the stories of Black veterans be part of our history curriculum?

These are fully American stories.

These are part of the reality of American history.

For me, as a historian, the thing I worry about is that people will think of history as something that just gets debated on cable TV shows.

That's not what history is.

It's a scary time to be a historian.

I mean, to see things in the news where politicians are getting up and proposing that certain books not be taught, that certain histories not be taught or be taught in ways that are entirely antithetical to how professional historians approach it.

And in terms of parents who might be worried about children learning about race or racism at too early an age, for people who have children of color, it's unavoidable.

Right?

We learn about this very, very early on.

There's no way to avoid it.

And I think that's part of what it means to be a citizen in a multiracial democracy.

History is one kind of foundational point that we've tried to use as a way to give our kids a sense of what that has looked like and how they can hopefully help our community, help the country move in different and better directions in the future.

-Our next author also leans on American history but uses it to carve out a dramatic triple-braided storyline.

Our other winner for Fiction, Geraldine Brooks, tells the story of one of the most dominant racehorses in the history of the sport and tells that story from the perspective of three different points in time -- most notably, the 19th century and the Black enslaved people most responsible for the horse's success.

Brooks utilizes the other timelines to remind readers of the racist horrors perpetuated by American slavery.

Simply titled "Horse," Brooks' novel brings her journalistic curiosity in partnership with her deep passion for the drama at the heart of all historical events.

-Horses are a prey species.

When you can get that interspecies bond of trust with an animal that instinctively fears you, when it happens, it's magical.

She's very tolerant of my out-of-tune singing.

♪ Pony girl, pony girl ♪ ♪ Be my pony girl ♪ ♪ Giddy up, giddy up, giddy up, whoa ♪ ♪ My pony girl ♪ So, I've become a horse obsessive.

I'm not getting any work done.

And I get invited to a donors lunch at Plimouth Patuxet Museum.

And I just happened to be seated at the same table as a gentleman from the Smithsonian Institution who had -- who was regaling his luncheon companions with the story of how he had just had the odd task of delivering the skeleton of the greatest racehorse of the 19th century from a forgotten place in an attic in the Natural History Museum to pride of place at the International Museum of the Horse in Kentucky.

And as he started telling the story of this extraordinary horse and then what happened to the horse during the Civil War, I was absolutely riveted.

My lunch was uneaten.

My companions no longer had a scintilla of my attention.

All I wanted to hear was the story.

He was saying about how famous this horse had been in the 19th century, such a celebrity that they buried the horse in a coffin, which is an extraordinary undertaking.

He was so fast, and the competition between him and the other great racehorse of the era was so intense that they mass-produced stopwatches so that people could time these races.

When Lexington died, his obituary ran over six broadsheet pages, everybody telling anecdotes of their associations with him and comparing him to other horses.

And it was really -- That was -- That was the motherlode of research.

Now, what was not so easy was researching the lives of the people who were mostly responsible for the success of this horse.

And these were Black horsemen, highly skilled trainers, grooms, jockeys -- many of them enslaved or formerly enslaved.

And I hadn't realized that when I set out to write a story about a racehorse that I would wind up writing a story about race.

Once I knew how absolutely integral to this massive national passion these Black horsemen were and how much the wealth and prestige of the white thoroughbred owners rested on their plundered labor and expertise, there was no honorable way not to foreground that story.

So once I knew that I was going there, I then drew on my own knowledge of horses to say, who is the most central person in the life of the horse?

It's not the owner.

It's not the jockey.

It's not even the trainer.

It's the groom.

It is the person who is coming into the stable in the morning with the food.

It's the person who is bathing the horse's legs when the horse is hot.

It's the person who sleeps in the stall if the horse is sick.

And that is the footfall that the horse recognizes.

♪♪ "'You're not fixing to let them take him away from us.'

'What do you think?'

"The horse never was in my name.

We got no proof I ever owned him, so we got no choice.

We got to stand and watch while the best horse I ever trained just go walking right out of my stable.'

'We can't,' Jarret murmured.

'Son, do you think I like it?

Not one bit.

But you tell me -- how do we stand against it?

Warfield and Viley?

They got the town in their pocket.

What have I got?'

'You got Darley.

And you got me.'

'I don't got you, boy.'

Harry reached up and grabbed his son by the shoulders.

'Dr.

Warfield got you.

Could be you he's fixing to sell... instead of the horse.

Don't you know that?

And I'd have had no say in that, neither.'"

♪♪ [ Horse snorts ] To be honest, at first, even much as I wanted to write about a horse, I thought this might be a better story for my husband, Tony Horwitz, who was a narrative historian who loved the Civil War period.

And he looked into it, but he just found that there were too many voids in the historical record, particularly about the Black horsemen.

Their lives were just not documented in the way the details about the horse were documented.

So it was going to be a different kind of story.

You could follow the line of fact, but when the line of fact frays and fades to nothing, the only way to engage with the story is by imaginative empathy.

You take as much as you can know, and then you have to fill in the voids with a speculation about how it could have been.

I am super aware of the discourse about white writers writing Black lives, and I suppose I could have centered the narrative on the owners of Lexington, who were fascinating characters, but I just thought that that would be to erase the contribution of the Black horsemen again.

♪♪ There was kind of a mean re-- I think it was intended to be a mean review on Goodreads, which I don't go to, but somebody pointed it out to me, saying that the book read like a white woman writing for white women.

And I am absolutely fine with that, because that's what an ally should be doing.

Speak to the people who will listen to you.

I don't have to tell a Black person about the evils of slavery or the -- the entrenchment of modern racism.

They know it.

They live it.

But my readers may be.

A lot of them privileged, middle-aged white women like myself.

Maybe they haven't had a chance to delve deeply into this history or they haven't been as lucky as I am to have Black friends that will speak honestly about their lived experience with me.

And so that's what I can do.

I can stand and speak to people who can hear me.

♪♪ Tony Horwitz was on a book tour in 2019 when he died suddenly.

And he had loved this book that I was working on because he loved that period so much, and he helped me a tremendous amount because he was a really proficient archive diver.

When he died, of course, me and the boys, my two sons, were just sideways.

I set the book aside.

And, um -- And then I realized that I needed to finish it.

I needed to finish it so that I could dedicate it to him.

♪♪ -Our Anisfield-Wolf Book Award winners told stories of people as their genuine selves.

Our Lifetime Achievement Award winner made a career of it.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault's name is easy to recognize through bylines and television and radio appearances.

A longtime journalist with a résumé that includes CNN, The New York Times, and PBS, she told the stories of Black people around the globe that so many news organizations failed to tell.

Alongside her high-school classmate Hamilton Holmes, Hunter-Gault desegregated the University of Georgia, and the two became the first Black graduates of the school in 1963.

Charlayne is a mother, a wife, and a loyal friend.

That's how she sees herself.

She may not like to admit how others see her -- as a civil-rights legend, a hero, an icon.

[ Charles Wright's "Express Yourself" plays ] -♪ Hey ♪ ♪♪ ♪ Express yourself ♪ -I decided on my 81st birthday that I needed to give myself a present.

This is part of our history.

♪♪ We didn't have a lot of preparation for what we might expect.

As we were walking in, a group of students had assembled.

I think they were mostly boys, and they were yelling ugly words.

My elementary school was segregated.

Every year, our Black school would have a fundraiser to help make up for the deficits, and whichever family raised the most money, their child would be crowned king or queen.

And within a short while, I heard, "And now our new queen is Charlayne Hunter."

But the crown.

I loved the crown.

I put on that crown.

I wore it every day to school for several days until my girlfriends got so sick of me that they used to tease me badly, and I finally took off the physical crown, but the notion that I was a queen took up residence in my head.

And so when I walked onto the campus of the University of Georgia and the students were yelling -- the N-word, "Go home!"

I was looking around for who they were talking about because I knew who I was.

I was a queen.

So I'm wearing my crown all the time.

[ LL Cool J's "Mama Said Knock You Out" plays ] ♪♪ As the years went on, there came a time when we were celebrated at the University of Georgia.

They named a building for the two of us -- the Holmes-Hunter Building.

But there was a governor who was the governor of Georgia when we had applied to the university.

And he had said, "No, not one," meaning not one Black student will ever be allowed to attend the University of Georgia.

Again, don't call it a comeback.

I've been here for years.

Because there came a time when that governor came and apologized for having said, "No, not one."

-♪ Don't call it a comeback, I been here for years ♪ ♪ I'm rockin' my peers, puttin' suckers in fear ♪ ♪♪ -I'm very frustrated with this move to stifle -- let's put it that way -- so much of our history because it's what has kept people like myself and Hamilton Holmes and so many others...

Uh...

It helped us to realize our dreams.

And when you take those things out of our history, you are attempting -- not, I don't think, being successful -- but you are attempting to remove our armor because our history is our armor.

♪♪ ♪♪ I'll never... stop believing that even though he made his, um.... peace... ♪♪ He made his peace with the university.

But I think... that although he was a medical doctor who once took care of my knee when it was hurting -- He was an orthopedic specialist.

I think PTSD took him away.

And I just -- I just have a hard time.

♪♪ I have a hard time processing that.

♪♪ ♪♪ -It's her debut, in other words.

Charlayne, welcome.

-Thank you, Jim.

You've talked about previous accounts of slavery being simplistic.

Here in Georgia, in the rural areas, whole towns are shutting down.

What is the song about?

-Mandela.

-Mandela?

-When Nelson Mandela was about to be released from prison... And I start by saying, "Mr. Mandela, it's such a pleasure to be here to interview you."

I said, "You know, I come out of the American civil-rights revolution."

Before I could get it out of my mouth, he said, "Oh!

Do you know Miss Maya Angelou?"

Now, the truth of the matter is, I didn't know her personally, but I knew her work, so I thought it was okay for me to say, "Oh, yes."

[ Laughs ] Now, everybody's looking for a scoop, right?

I had no idea my scoop was coming when I had this conversation, but he said, "Well, we read every one of her books while we were in prison."

Now, everybody wanted to know something personal Mandela had done that helped him get through 27 years in prison.

I had it!

[ Laughs ] I had a scoop!

♪♪ I don't think of myself as anything special... other than as a wife... of 52 years and a mother of two wonderful children.

Now, you see, I can't do that.

I can't do that with one hand.

-That's where the nails come in.

-Mother, who's your biggest champion?

Me.

♪♪ So, to me, it's just my mom and her job, really, in a way.

But then I really appreciate what she's done historically as a writer, as a woman, as a journalist, as a champion for people who are underserved, under-viewed, not seen enough, whose stories aren't told enough.

I tried to leave school one time.

I didn't feel like going to college anymore.

[ Scoffs ] Good luck with that one.

Like, she didn't fight so hard to get into her school and, you know, go through what she went through for me just to go, "I don't feel like it anymore."

That wasn't really an option.

So, yes, I have been influenced.

♪♪ -She was not in the way.

-Ooh!

I'm sor-- Ooh.

-Ohh!

-That's it.

-If there's anything that I would like to take away from my life as a journalist is that I have tried to report on people... as they see themselves.

It's very important for you to know the people you are covering.

You know, when I hear that there are younger journalists who are looking at the work that I've done and, in a sense -- maybe I can use the word "inspired" by it...

...I just -- I'm honored.

Um, at the same time, I'm impressed with what so many of them are doing, and that's why I called for a coalition of the generations, because I've had my successes and my awards and recognitions... "In appreciation of..." ...and all of that.

But I think that... the thing that... helps me the most keep on keepin' on is that there is a younger generation that's coming after me.

♪♪ "Mr. Jordan helped lead us through the crowd of students yelling ugly racial epithets as we walked on campus to register for classes.

With this history in my head and heart, my path forward includes working to ensure that the doors of my alma mater are open even wider to Black students.

And so, as I reflect on the 60th anniversary of my university's desegregation as a Black person and a woman, as a wife and mother, as a sister, aunt, and citizen remaining true to my calling as a journalist, I leave you with the question -- what can we all do to keep working toward a more perfect union?

Go, Dawgs!"

♪♪ -We thank this latest generation of authors for celebrating diversity, fighting racism and ignorance, and protecting our narratives, passing them down to our future literary giants.

It's meant the world to me to be able to help honor these icons for nearly 30 years, doing my part to bring these stories into the forefront.

While my time on the Anisfield-Wolf jury is coming to an end, I'll continue to be thankful for these words on the page that protect our stories... as Charlayne says, that protect our armor.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Funding of the Ideastream Public Media production of "The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards" was provided by the Cleveland Foundation.

Support for PBS provided by:

The 88th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards is presented by your local public television station.

Distributed nationally by American Public Television