Innovation Makes Beloit

Clip: Special | 9m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

Early residents built up their city through Beloit College and industrial innovation.

Residents of Beloit collaborated to create a college, based on ideals from Yale College. At the same time, agriculture thrived and blossomed into industries like Fairbanks, Morse & Co. and Beloit Iron Works.

Wisconsin Hometown Stories is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

Innovation Makes Beloit

Clip: Special | 9m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

Residents of Beloit collaborated to create a college, based on ideals from Yale College. At the same time, agriculture thrived and blossomed into industries like Fairbanks, Morse & Co. and Beloit Iron Works.

How to Watch Wisconsin Hometown Stories

Wisconsin Hometown Stories is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

[ambitious orchestra] - By the mid-1800s, Beloit was attracting new residents and garnering media attention.

The inaugural issue of the Chicago Magazine in March 1857 hailed the many virtues of this burgeoning city on the Rock River.

- Chicago Magazine: "There's no city "in the circle of our acquaintance, "where its business facilities, "educational advantages, "and the high moral tone of her citizens "has made us feel more in love with it and its people than this."

- The magazine sang the praises of Beloit College, a dream of the New England Emigrating Company.

Ten years after the founding of Beloit, one citizen's generous donation and influence made the college a reality.

- Fred Burwell: Lucius Fisher was an early settler in Beloit.

He was from Vermont.

As a young man, he had hoped to go to college and was not able to.

But that stayed with him.

And he was very, very much in favor of founding a college in Beloit.

And he helped get that going by offering land for the college.

And he convinced some other settlers to donate the land, as well.

And so, he was vital to securing a spot for the college.

- Fisher and other community members donated land on a bluff overlooking the Rock River.

Mounds made by the ancestors of the Ho-Chunk marked the grounds, including one that appeared to be in the shape of a turtle.

[warm violin] The Wisconsin Territorial Legislature granted the college their charter in 1846, making it the second oldest college in the state.

Upon its formation, Beloit College had no buildings, professors, or students.

Local industrialist Sereno Taylor Merrill stepped up.

- Fred Burwell: Sereno Taylor Merrill was an educated man.

And as the college plans took shape, he agreed to train some students for college.

And the idea was that they would take entrance exams based on Yale College.

And by the fall of 1847, he had about a half a dozen students ready.

And they entered Beloit College officially.

- That same year, the school started construction of the first building on campus, later known as Middle College.

Beloit College looked east for their first professors and hired two recent Yale graduates.

- Fred Burwell: Beloit College and the city of Beloit celebrated that Yale connection and used it.

Beloit College became the "Yale of the West."

Having a school that equated itself with Yale meant something.

- As the college grew, it began to diversify.

An early president expressed a progressive vision for the student body.

- Fred Burwell: President Chapin, in his inaugural address of 1850, wrote that "A college must stand with open door to youth of every rank and condition in life."

In the fall of 1895, women entered the college.

Within a few years, the valedictorian of the class was a woman.

The college has done a good job of attracting students from all walks of life and backgrounds.

And that's been true from early on in the college's history.

- Along with development of Beloit College, the city's early economy took shape.

Agriculture dominated the city's early industry, but that was quickly overtaken by manufacturing growth as early rail access allowed for goods to be sold beyond the Beloit area.

- John Patrick: All the goods that they made were farm-oriented or products that could be sold or used strictly locally.

But once the train comes, then the world is your marketplace.

[dramatic, driving music] A lot of industry expanded in Beloit, and it made a whole difference in the growth of the town.

- Beloit's growing industries attracted new businesses and innovators hoping to build upon Beloit's success.

- John Patrick: Leonard Wheeler was a missionary for the Ojibwe Chippewa Indians on Madeline Island at one time.

And those people were fishermen.

So, he taught them how to farm.

And he knew that he needed water.

He needed he needed to grind grain.

And so, he invented a windmill that could do all these type of things.

And he did that with success.

Reverend Wheeler had children and he wanted to educate his children.

So he sent his son, William, to be educated at Beloit College.

When William Wheeler convinced his elderly father that they could sell those windmills, Reverend Wheeler's family moved to Beloit and they went in the business of manufacturing windmills in the 1860s.

And at the same time, of course, the railroads were heading west.

And every steam engine, every time they stopped, they needed water.

They needed a windmill to pump water.

That was the real success of the Eclipse windmill.

It became the number one windmill in the country.

- The Eclipse Windmill fueled industrial growth in Beloit.

In the 1890s, the Eclipse Windmill Company merged with two other businesses to create an industrial powerhouse in Beloit.

- John Patrick: William Wheeler sold his interest in the Eclipse Windmill Company to the gentleman who was selling his windmills.

They were sold nationally by a guy named Charles Morse.

- Originally in the area as a salesman for Fairbanks Scales, a growing Vermont business, Charles Morse quickly saw an opportunity in Beloit.

In 1893, Morse combined Fairbanks Scales, Eclipse Windmill, and local business Williams Steam Engine Company into one new business called Fairbanks, Morse, & Company.

At the same time, another business was emerging in Beloit: Orson E. Merrill and George Houston's Iron Works Company.

- Beatrice McKenzie: Early on in the business, the foundry made the water wheels, horseshoes, spokes, all sorts of little parts of other machines.

It's amazing to me that they grew so quickly that they went from being a foundry that made equipment for other factories-- including paper mills-- to actually making paper mills.

And they sent a complete paper mill to the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago.

It took 26 railroad cars of equipment.

- John Patrick: So, people from all over the world came to Chicago and saw the Beloit Iron Works machine.

The Beloit Iron Works machinery became the standard of the world.

- Beatrice McKenzie: I think what made Beloit ideal for some of these industries was its location in the Midwest.

So, it was close to Milwaukee, it was close to Chicago, it was close to the Twin Cities.

It was on the rail lines.

But I think another aspect of it is that it had this small coterie of people making decisions.

And part of their task was accumulating capital for new businesses.

Beloit's population grew so quickly that actually, in the period between the census of 1890 and 1900, Beloit's population grew by 65%, whereas it was only 21% for the entire United States.

So, the population was growing quickly.

- Businessman Arthur P. Warner contributed to Beloit's industrial landscape with his company's invention of the speedometer and trailer brake technologies.

In 1909, Warner assembled and flew an early airplane, earning Beloit the title of "first in flight" in the state of Wisconsin.

- John Patrick: After the turn of the century, Beloit, for a small town, became one of the best industrial towns in the country.

- In the 1930s, Beloit's agriculture and manufacturing industries came together to develop a unique food invention.

While processing feed for farm animals, workers at the Flakall Company realized that the puffed-up cornmeal coming out of the machine made a tasty snack.

The Flakall Company soon sold these puffs as the "Korn Kurl."

Other companies caught on and produced similar cheesy treats that are still one of America's favorite snacks today.

- John Patrick: Everybody had a job.

We manufactured everything for the world.

By the time I was a young man, and I wanted to go look for a job, I could have got hired five times in five days.

It's just the way Beloit was.

- With a renowned college and robust industries, Beloit residents took pride in their city.

This sentiment was reflected on a billboard in downtown that read "What Beloit Makes, Makes Beloit."

Video has Closed Captions

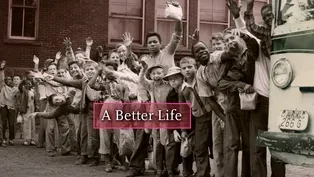

Across decades, Beloit’s newcomers find opportunity and community through education. (7m 7s)

Video has Closed Captions

Beloit’s residents revitalize their city and return to the confluence where it all began. (10m 39s)

Video has Closed Captions

The confluence of two waterways drew the Ho-Chunk Nation and settlers to the Beloit area. (7m 26s)

Video has Closed Captions

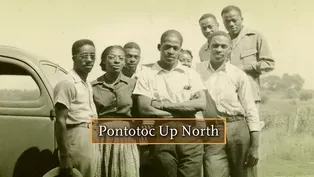

Southern Black families moved to Beloit to escape injustice and seek job opportunities. (9m 27s)

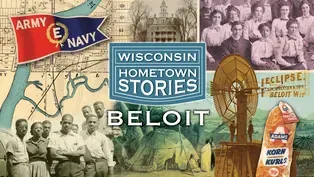

Preview - Wisconsin Hometown Stories: Beloit

Stories of industry, education and community pride illustrate Beloit’s rich history. (30s)

Video has Closed Captions

John Patrick’s family grocery store fed a hunger for yellow margarine on the state line. (2m 40s)

Program Extra: Growing Up on the Rock

Video has Closed Captions

Ron and Gary Delaney fondly remember growing up on the Rock River. (3m 36s)

Program Extra: Keeping Flats History Alive

Video has Closed Captions

Three former Fairbanks Flats residents reminisce growing up in their community. (2m 25s)

Video has Closed Captions

Beloit’s industry, college and community each contributed to World War II victory. (8m 31s)

Youth Media Extra: Deportation

Video has Closed Captions

Students examine the history of deportation in the United States. (5m 48s)

Video has Closed Captions

Students examine the history of Latino-owned businesses in Beloit and nationally. (4m 22s)

Youth Media Extra: No Entiendo

Video has Closed Captions

Students examine the history of accommodations for Latino students in schools. (5m 52s)

Youth Media Extra: Tú No Eres De Aquí

Video has Closed Captions

Students examine the history of discrimination against Latinos in the workplace. (5m 30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWisconsin Hometown Stories is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin