August 21, 2023

8/18/2023 | 55m 22sVideo has Closed Captions

Anthony Fauci; Jemima Khan; Emily Witt

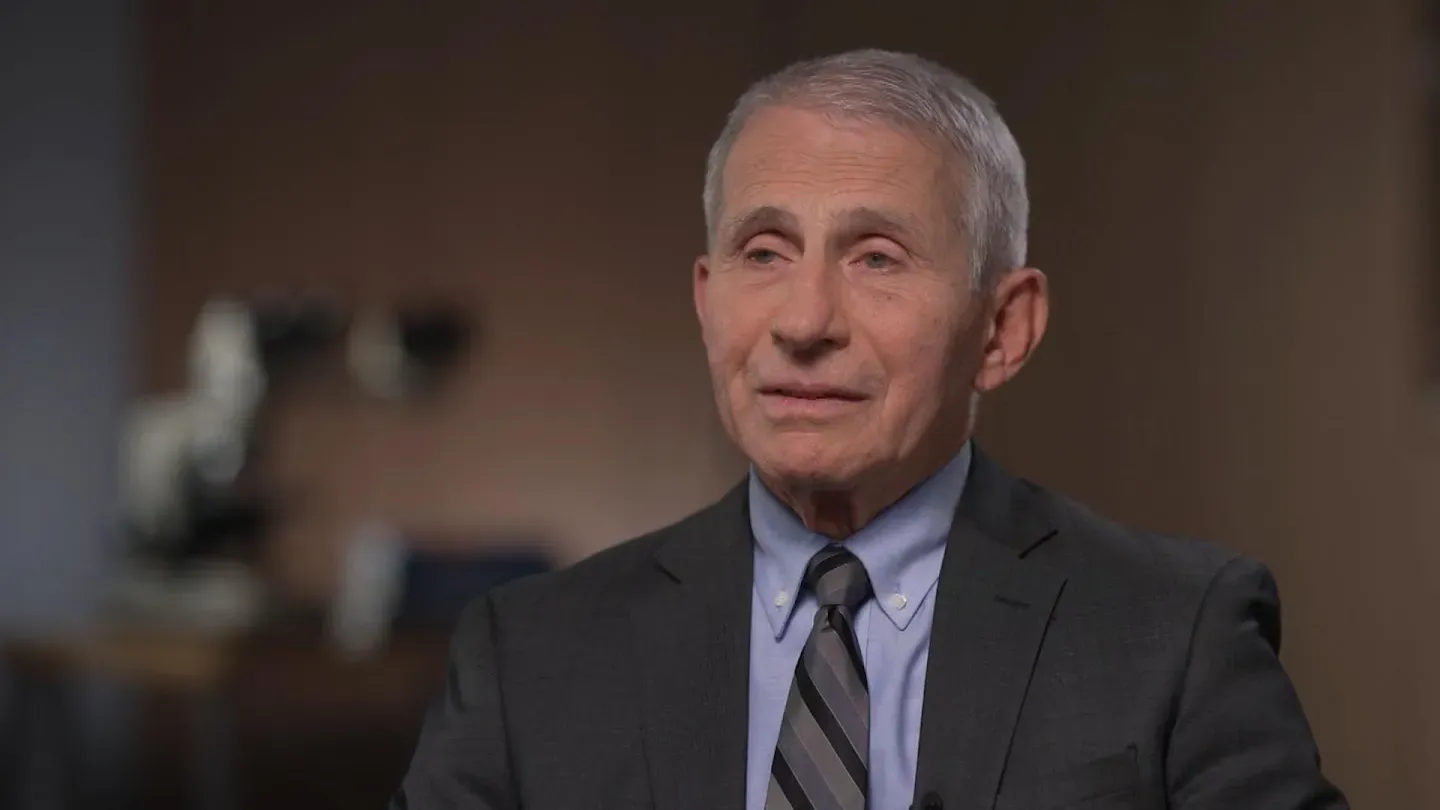

Three years after COVID-19 swept the globe, Christiane meets with Dr. Anthony Fauci in New York. Jemima Khan’s explores themes of religion, family and arranged marriage in her new cross-cultural movie, “What’s Love Got to Do with It.” The New Yorker's Emily Witt discusses advancements in fertility research.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

August 21, 2023

8/18/2023 | 55m 22sVideo has Closed Captions

Three years after COVID-19 swept the globe, Christiane meets with Dr. Anthony Fauci in New York. Jemima Khan’s explores themes of religion, family and arranged marriage in her new cross-cultural movie, “What’s Love Got to Do with It.” The New Yorker's Emily Witt discusses advancements in fertility research.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[air whooshing] [inspirational music] - Hello everyone and welcome to Amanpour & Company.

Here's what's coming up.

[air whooshing] - If we go into the next pandemic in a discombobulated way where no one knows what the truth is or who's saying what, it's gonna be even worse.

- [Christiane] Dr. Anthony Fauci, his experience as Chief Medical Advisor, and why science is the only way to get through the next pandemic and what went right and wrong handling COVID.

Then- - Dare I ask, what about love?

- You grow to love the person you're with.

- What, like Stockholm syndrome?

- [Christiane] What's Love Got to Do with It?"

Filmmaker Jemima Khan talks to me about arranged marriage, and her multicultural rom-com ahead of its U.S. release.

Also ahead- - It's just this kind of black box that science doesn't quite understand.

- [Christiane] The future of fertility.

Investigative journalist Emily Witt takes Michel Martin to the cutting edge of reproductive science.

[inspirational music] - [Announcer] Amanpour & Company is made possible by the Anderson Family Fund, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim, III, Candace King Weir, Jim Atwood and Leslie Williams, the Family Foundation of Leila and Mickey Straus, Mark J. Blechner, Seton J. Melvin, Bernard and Denise Schwartz, Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities.

Barbara Hope Zuckerberg.

We try to live in the moment, to not miss what's right in front of us.

At Mutual of America, we believe taking care of tomorrow can help you make the most of today.

Mutual of America Financial Group, retirement services and investments.

Additional support provided by these funders, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

- Welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Christiane Amanpour in New York.

Three years after this strange new killer disease swept the globe, the world is now moving on from COVID and all that pain and loss.

President Biden confirming America's state of public health emergency will end on May 11th, while the UK has shut down its COVID app that was required to prove vaccination status to enter certain public spaces.

The toll is staggering to contemplate.

Official estimates say the virus killed more than a million people here in the U.S., and about 7,000,000 worldwide.

But my first guest tonight says that is an underestimate.

The real death toll could be 20,000,000 and it would probably have been double that without the vaccine.

Dr. Anthony Fauci was undoubtedly the face of the COVID response as Chief Medical Advisor to the President.

We met up here in New York as he received the prestigious Calderone Prize from Columbia's Mailman School of Public Health.

Dr. Fauci, welcome back to our program.

- Thank you.

Good to be with you.

- And obviously congratulations on this major award for public health.

At the gala event, you gave a pretty profound and passionate plea to the public health community in the audience.

What were you trying to tell them?

- Well, the point I was trying to make is that we had been through an extraordinary ordeal with the three and a quarter years of COVID-19, and there is a lot of activity now looking at lessons learned, what went right, what went wrong, how can we better prepare for and respond to future pandemics.

And unfortunately, I think as everyone realizes, there's been a lot of politicization that has gone on over these last three years of things that should have been purely public health issues.

There's been a lot of misinformation and disinformation and distortion of truth and reality.

My plea to them was that we really needed the serious academic scholarly approach to an analysis of what went on rather than giving way to some of the obvious politicization that goes on.

We're living in an arena now, which is very troubling, and that is what I call the normalization of untruths, where there is so much distortion of reality that the public gets inured to it.

It's kind of like it's normal, it's natural, no problem.

People are just saying that.

That's a very dangerous situation to get into because when you do accept the normalization of untruths and you don't have pushback from people who actually are using evidence-based and data-based statements, then reality gets totally distorted.

So I think that's dangerous not only in the arena of public health, I actually think, not to get too melodramatic about it that it really is, sort of erodes at the foundations of democracy.

- But you have had to go through and you've talked about it.

I mean, let me just read what you said to Congress.

"I've had threats upon my life, harassment of my family, my children, obscene phone calls because people are lying about me."

I.e., lying about you and about the science.

You have a phalanx of guards 24/7 all keeping you safe.

What does that say to public health officials and to yourself about waging this war in the future or this struggle for life?

- Well, to me it tells us we have to do it and we cannot be dissuaded from doing it because of the threats.

I am a visible public figure, but many of my less well-known colleagues who speak out the truth about things almost instantaneously from the time they do that, I don't know whether it's bots or real people start just making harassing threats to them.

We can't yield in the face of that because it's such an important issue, and that's one of the reasons why I will continue to try and inspire and encourage particularly younger people to get involved in medicine and science and public health and perhaps even public service, which I think is so important.

- Because the key obviously is right, again, lives.

What keeps you up at night about how, given the experience of what happened during the COVID pandemic nationally and globally, the next pandemic will be addressed?

- Right.

That's what I worry about.

If we go into the next pandemic in a discombobulated way where no one knows what the truth is or who's saying what, it's gonna be even worse than what we've seen right now.

I tend to look at this in two buckets of preparedness and response.

One is the scientific preparedness and response, and the other is the public health preparedness and response.

What was the resounding success was the science.

I mean, to be able to have the sustained investment in basic and clinical biomedical research that allowed us literally within days of getting the sequence of the virus to begin the vaccine development program, to be in a phase one trial in 65 days and at the end of 11 months to have a vaccine that was safe and effective, that is beyond unprecedented.

I mean, if we were having this conversation 10 years ago, I would've told you that's nuts.

There's no chance that that's gonna happen.

That was the result of a sustained investment in basic and clinical biomedical research where what did not go as well was the public health, the infrastructure, the communication, the ability to get data in real time as opposed to waiting weeks and months to make the data that would inform decisions you'd have to make.

That has to improve.

- The COVID report that's recently been released by a bipartisan group of mainstream medical community and others have have listed a bunch of things that could have gone better.

"COVID war revealed a collective national incompetence in governance.

There was a delay in responding because authorities could not track the outbreak's progress until patients showed up in the ER.

Poor communication during both the Trump and Biden administrations."

And here, "500,000 deaths could have been prevented even though us spent $5,000,000,000,000."

You've been asked a lot about this quote unquote, "Monday morning quarterbacking."

Are these valid points?

- I think they are for the most part valid points.

And if you take each one of them, you could see what the underlying reason for that was.

We have in our country, first of all, the idea of being able to get data in real time.

It is embarrassing that other countries like Israel and South Africa and the UK have health systems where data is fed in, in real time and you know what's going on the next day or the next week.

Whereas it takes us sometimes months to figure out what happened.

And when you're dealing with a rapidly moving pandemic, that is unacceptable.

That's the first thing.

The other thing is the divisiveness and the politicization that occurred where you had from the leadership from the beginning, a denial that this was a problem.

And that's when I had to come into an unwanted conflict with the President when he was saying, "This is gonna go away like magic.

It's gonna be gone, don't worry about it."

And I had to come forth and say, "That's not the case, I'm sorry.

I don't mean any disrespect for the presidency, but this is not correct."

The other thing that they bring up is the fractionated nature of our approach.

One of the beauties of our country is that we're a very diverse country geographically, culturally, economically.

And we have 50 states and more territories who have the ability to do things their own way.

That is a problem... That's beautiful when you want to be able to accommodate the diversity in the country, but when you have a common enemy, the virus, and you have people doing things in multiple different ways, that is not a coordinated response to a pandemic.

So, many of the things that you mentioned, Christiane, are really absolutely valid points.

- There were many instances, and we could play many and repeat many, you're obviously very familiar, but the 50 cuffs with with with people in Congress, presidential candidates, senators, governors, DeSantis, and other people who just basically blamed you.

They basically blamed you.

They said everything you did was contrary to saving lives as if you were in full charge.

So, I realize you're gonna say, "Well, no, I wasn't in full charge," but I wanna know what you think you and the community got wrong?

Was the closing of the schools to draconian?

How much of a delay did the fact that nobody fully understood the asymptomatic spread of this, nobody figured out that it could actually bust through certain vaccine levels as well.

What are the real takeaways and the real lessons for the public health?

- Yeah, I think we have to get away from the blame game because so many of the things that you have mentioned were unknowns at the time.

It's so easy, and I made that comment in my response to one of the questions that Davis Wallace-Wells asked me in the- - This is in "The New York Times Profile."

- In "The New York Times Profile."

And I didn't mean it as an affront to him, but I said, "This is really big time Monday morning quarterbacking here," which is what it is.

So, rather than have a blame game, and that's one of the things that we have to stay away from because there were things that happened and it was a moving target and there were things that you did not know at the time and you had to, out of necessity, make a decision.

And sometimes the decision was partially right.

For example, let me give you an example of a partially right decision.

I think the idea when you were having trucks that were cooler trucks pulling up to hospitals in order to put bodies in because the morgues were overflowing and the hospital beds were being challenged that you had a triage, you had to shut down.

I don't think anybody who has any realistic evaluation knows that you gotta do something dramatic.

Once that's done, then the thing that you need to now go back and analyze, I don't think anybody would argue with the fact that you had a shut down, is how long you keep the shutdown and how complete it is.

How does that relate to schools when you shut down schools if you do, and I have been very vocal about this, and I think the people who like to point fingers, I say, go and look at the tape, [chuckles] the tail of the tape, when I kept on saying over and over again, we've gotta get the children back to school as quickly as possible.

We've gotta get them in school safely and we've gotta make sure that they're not essentially out of school, at home getting all of the negative consequences.

Different parts of the country interpreted that differently.

There were schools that stayed closed far too long and longer than they should have, and there were those that essentially didn't close at all.

My daughter is a school teacher in New Orleans, they closed down for two weeks and were essentially open for the rest of the time, and other schools- - And the result was?

- And the result was they didn't do too badly.

I mean, the kids got infected.

A lot of them did virtually.

It was very difficult to determine and say, well, if you shut down this long, you get no negative effect on the child, and minimal effect on the infection, Those studies weren't done.

It was just trying to do as best as you can in the circumstances that you were in.

- Can I ask you, because you are no stranger to very, very difficult public health decisions.

Obviously, we all know you came to massive prominence during the HIV.

There was a huge backlash from the community against you at the beginning, and then you sat down, talked to them and it became an amazing partnership and you were responsible for the antiretrovirals, and it had an amazing effect on public health.

Can you describe or contrast the backlash that you had from the AIDS community at the beginning compared to the MAGA community, or whoever was against you in COVID?

- Yeah, it was as different as apples and watermelons.

It was really different and the differences are sometimes misunderstood.

Back in the eighties when we were dealing with the mostly young gay activists community, what the point they were trying to make, they were trying to get the attention of the scientific community and the regulatory community to say we want to be part of the process of the design of clinical trials, of attention paid to this, of the rigidity of the regulatory process because the scientific and regulatory process worked extremely well for other diseases, but was ill suited for the emergent nature of a disease that was mysterious and that was killing young men.

They didn't even know they were infected until years later when they were starting to deteriorate from a health standpoint.

They wanted to say, "Listen, you're having clinical trials, there are no real drugs available.

We want to be part of the design of the clinical trial process.

We want less rigidity in the regulatory process."

So what they did to gain attention, they became theatrical, iconoclastic, confrontated, disruptive.

They got my attention, they did.

And when I listened to what they were saying, it was eminently clear to me that what they were saying was making absolutely perfect sense.

And if I were in their shoes, I would've been doing the same thing that they were doing.

That turned me around completely and made me embrace their activism and say, "Now we've gotta change the system.

We've gotta get you involved from the ground floor in the design of the trials, in the regulatory process so that we can work as a team."

That is very different from a group that is pushing back with misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories, outright lies, essentially saying vaccines don't work, making up things that we're putting chips in vaccines, getting people to not want to essentially utilize life saving interventions.

That was very painful to me as a physician because my entire DNA has been to alleviate suffering and save lives.

And when you have people who are pushing back against you, but what they're pushing back against is trying to give disinformation that would get people not to utilize lifesaving interventions.

That's a big difference between the anti Fauci attention getting that the gay activists did, which was based on a noble endpoint versus pushing back and spreading disinformation.

They're two entirely different.

- Obviously the whole lab leak theory and the origin of this, I think you still say it's not clear.

- Right.

- But what is your view today about that?

- Yeah, well first you have to keep an open mind because we don't know definitively what it is.

And when you don't know definitively, you've gotta keep an open mind to all possibilities.

If we do get a definitive determination, I will certainly embrace that fully.

Right now because we don't know what it is, instead of pointing fingers and blaming, we should be saying it's either one or the other.

That being the case, let's right now start doing things to mitigate against the possibility that this would happen again versus that would happen again.

And the two possibilities, as you know, lab leak versus natural occurrence.

Having said that with an open mind as a scientist, I have to look at the data and say, "Although either is possible, that doesn't necessarily mean they're equally probable."

And if you look at the data that's been accumulating over the last year or several months, even most recently, it's pointing much more strongly towards a natural occurrence, but it hasn't been definitively shown.

So, as long as that still remains the situation, you must entertain the possibility of both.

And that's exactly where I stand.

- So finally, how do you feel personally?

You've been through the wars, you've been through the ringer.

How is Anthony Fauci?

- I'm actually fine [chuckles].

I really am.

Certainly, it's been a a trying and difficult time, but as I've always said, and I mean that sincerely, as a physician and as a scientist and someone who cares deeply about individual health and public health, even at a global level, I just focus like a laser beam on what my mission and my goal is and my mission and my goal is to do whatever I can to safeguard the health and the safety of the American public and then, therefore indirectly of the world because we're such a leadership.

Everything else, quite frankly, Christiane, I mean that, is noise.

The noise of the attacks and even the somewhat amusing noise of the idolization.

But both of them are unrealistic.

I know who I am and I know what my goal is and that's how I get through this and it doesn't, the only thing that I don't really like about it is the impact it has on my family, my wife and my children, when you get attacks like that.

But apart from that, the rest of it is noise.

- Thank you very much indeed, and congratulations on this honor.

- Thank you very much.

It's good to be with you.

- A true public servant.

Next to the role of rom-coms in modern life, the genre is experiencing a surge with a lot more diversity in depicting different cultures, and with more female perspectives.

The producer and screenwriter Jemima Khan explores religion, family, and arranged marriage in her cross-cultural movie, "What's Love Got to Do with It?"

It follows a young British woman documenting her friend's assisted marriage to a Pakistani woman.

Some of it is based on her own experience as the wife of Pakistan's cricketer, turned Prime Minister, Imran Khan.

- So, you want ideas for your next film?

- I could follow my childhood friend to marry a stranger chosen by his parents.

- "My Big Fat Arranged Wedding."

- "Meet the Parents First."

- "Love Contractually."

- [Both] Huh.

- Mo here, Mo the Matchmaker.

- No photos?

- No, no photos yet.

You're thinking with the Lulu, you need to be thinking with your Nunu, okay?

- A big success in the UK, the film opens here in the U.S. next Friday.

We sat down to talk about why telling this kind of story really does matter.

Jemima, welcome to the program.

- Thank you for having me.

- I need to start by saying that we've been friends for a long, long time, more than 20 years.

I knew you when you were married to Imran Khan and afterwards.

I didn't know that you were planning on writing this film, but where did you get that inspiration?

- It's taken a long time.

It took me over 10 years from having the first idea to seeing it on screen.

And it's obviously inspired by my 10 years that I spent living in Pakistan.

I mean, pretty much every character I've met somewhere along the way on my journey and also every line, every joke, every anecdote is still pilfered from real life.

But it just took a very long time to realize.

- And you wrote it on your own?

- I did.

I have a production company.

I make documentaries and TV mostly for the U.S. and the UK.

So, I was doing this in my spare time.

It was very important to me to do it on my own because I felt that, well, apart from anything else, it was just a real challenge that I set for myself, but also I didn't want the sort of assumption that I'd just given the storyline and some ideas and hadn't actually done the real graft.

And boy, was it a graft.

- It's a rom-com with a twist.

- I'm glad you think that.

- Yeah.

- I mean, yeah, people have said that it's sort of subverted the genre of rom-com.

I'm a big rom-com fan in that I like rom-coms that are very grounded in reality.

I don't, I guess I'm not such a fan of broad comedy.

And one of the reasons why we went for a director who isn't actually known for his lulls [laughs], Shekhar Kapur- - [Christiane] Because his Oscar win, yeah.

He's the director, but he had done "Elizabeth."

- Exactly.

- Before.

- Before Working Title, - Yes.

- the same company that made this, but the reason we went for someone who is very interested in the kind of truth of the story was to add that layer of kind of authenticity and believability.

I call it a rom-com.

Working Title, who basically defined the genre rom-com, call it a rom-com.

He thinks it's a family drama 'cause it definitely has something hopefully serious to say behind the laughs.

- It's definitely a family drama, and I just wanna get back to your family because I know and you've mentioned in other interviews that when you went, you left university, you married Imran, you went and lived in his rather conservative Pakistani family in Lahore, right?

And you were all jammed together in one apartment with in-laws and the like.

And you and Imran were the only love match of that family, you say.

So, what did you see around you?

Assisted and arranged marriages underway?

- Yes, and I think that the film sort of charts that trajectory in terms of my understanding of what an arranged marriage might be in modern day Pakistan, or also in the West as well.

Ours as you say, was the only what they call love marriage, non arranged marriage in my ex-husband's entire family history.

I went there and moved in with, as is the tradition in Pakistan with his entire extended family.

So I lived with his father, his three sisters, their husbands, all their children.

There was something like 26 of us living in this one big family house in Lahore.

And so I got to see how arranged marriages worked in real life.

I also saw the children grow up and then have arranged marriages themselves when they reach their 20s, and I was kind of involved in that process.

I was sort of on the committee to select the suitable spouse or suggest, I shouldn't say select because it's become known as assisted marriage.

It's more about an introduction.

And what I realized throughout this period is that some of those arranged or assisted marriages, which were absolutely based on the idea of consent, were very romantic and based on a really deep love, but it's a different premise.

You don't start with love, you end with love.

They always used to talk about you better to simmer than boil.

You don't fall into love, you walk into love and it's sort of a different idea.

And I think the idea for the film came about because when I came back to the UK after 10 years, some of my friends were thinking of having kids.

They were in their early 30s and wanting to look for a suitable father for those children.

And we would have a conversation about what would happen if you were to take purely the love at first sight and the chemistry out of, that component outta the choice, who would your parents or even your friends choose for you, and what might that person be like and would it work?

And I thought, "Gosh, what would happen now if I hadn't had my backstory and I let someone choose for me?"

And that's where Lily James's character gets to after following the journey of her best childhood friend Caz, who's having an arranged marriage, and she finally defers to her mother and says, "All right, go on, have a go."

- So, that leads me to play the first clip that we have and this is Lily James's character...

Remind me of her name again.

Zoe.

- Zoe.

- Talking to Caz about all this over a game of ping pong back in London.

Let's play.

- Dare I ask, what about love?

- You know what, it's just a different way of getting there.

Now, you don't have to start with love.

You can end with love, and over time you grow to love the person you're with.

- Hm.

What, like Stockholm syndrome?

[Caz laughs] You know my parents aren't making me do this, right?

- No, I know.

That's why I'm so surprised.

- Do you know what the UK divorce rate is?

- No.

- I found out.

- 50%.

- 55%.

[Zoe laughs] And guess what it is for arranged marriages.

6%.

Boom!

- So look, she's an English girl with her English eccentric mother living next to a Pakistani English family.

What were you saying about the vision, the lens or whatever people talk about right now on these issues?

- I think it's very easy to be kind of from our sort of western viewpoint, quite disdainful about this seemingly outdated idea of arranged marriage whilst we also have quite, sometimes we're letting algorithms randomly select men for us, the dates for us, - On the dating apps.

- on the dating apps.

And I'm not sure that it's as easy to say one is right and one is wrong, and so I, and that sort of is...

I went in with those preconceptions when I first went to Pakistan.

I thought that it was a sort of medieval chattel swap that had no place in the modern age.

And I came away thinking, "Hm, there's something to this."

And there are some very happy arranged marriages I've seen.

And I think that we tend to have a somewhat blinkered idea where even in some of the mainstream films where they touch on arranged marriage, the arranged marriage candidates are really suboptimal and are kind of the butt of all the jokes, so I think I partly wrote this film as a response to a very common lament that I heard from my Pakistani friends in Pakistan, which is about how they feel their country and people are depicted on screen in the west, that western mainstream TV and films, whether it's like "Zero Dark Thirty" or a series like "Homeland," often it's the Pakistani and certainly the Muslim characters who are the shady ISI operatives or the terrorists or somehow backwards.

And so, we don't have any terrorists in our rom-com, and I think that's why I wanted to do something a bit surprising because when you look at the news and you, about Pakistan it's often seen as a very scary, dangerous place and scary, and scary, dangerous things as we know do happen there.

But there is another side to Pakistan and that's also a Pakistan that I experienced, which is a fun and colorful and joyous and hospitable place.

And I wanted to make a film that celebrated that, that displayed the beautiful older architecture, the music, the colors, the costumes, and the music was actually very special to me in particular, but I've, very long winded answer.

- Well look, it certainly hit a major nerve.

From what I gather from release to whenever you can measure it, it was the biggest grossing English made film for that period of time when it had its cinema released earlier this year in the UK and now it's going to be released in the United States.

But you got lots of lovely commentary from the community, which I've been sent.

Here's one.

"I stayed up all night with my parents having the most soul bearing conversation about their arranged marriage and their life back in the 90s in Pakistan.

After watching the film, it felt as if a border was broken, and through the generational divide it was love that liberated us."

And then another says, "The story is not just showing a British Pakistani family, but it's relatable to every South Asian community.

The real sides that are never shown in any other movies are seen in this.

Watching this movie was a real evaluation of family bonds and relationships."

Were you worried, were you at all fearful?

Was the company fearful that somehow this would miss the mark?

- I mean, if it had, and if British Asians or if Pakistanis in Pakistan and India had not reacted positively to the film, regardless of the box office, generally, I would've considered it a failure.

But we have been so lucky, and I feel so touched by the unbelievable outpouring of love for this film, particularly from the British Asian community.

And for me, that's why I made it.

I did say it was my love letter to Pakistan, but also to South Asia and to South Asian talent.

And so I had, so we've had so many messages like that on social media from people who've, where it's helped to have conversations with parents and people from a different, to family from a different generation.

And I feel incredibly heartened and touched by those messages.

- In the United States you have said in terms of the stereotype and a certain Islamophobia that's existed certainly since 9/11, how are you going to talk about it in North America?

- I understand the fear after 9/11.

Obviously, I understand that there is this fear around Islam and Muslims, but that's why I wanted to make this film and make a film where I showed Muslims who are very much not the baddies, which is reflects the absolute majority of Muslims in the world today.

And I hope that it will resonate in kind of mainstream white America, but I don't know.

- But that's really interesting, and it probably will.

I mean, there's a huge community there.

There's a huge community in Canada and this may land at the very right time like it did here.

But interestingly, I just heard that this year between Hollywood and all the other production centers, some 36 rom-coms are being released.

The genre is getting a surge.

- Yeah, I mean, ours was...

It's obviously a very diverse cast and it's a very diverse behind the camera teams.

Every single department had Pakistanis or British Pakistanis in it.

And we have a South Asian director and I think it's really important.

I do think things are really changing in terms of what gets made and what we see on our screens.

I think that there's been a massive shift in the last few years.

- As I think your star, Shazad Latif said, "It changes people's neural pathways when it-" - Did he say that?

- Yeah, in one of the interviews.

So I'm gonna play another clip that we have, which is, actually this time it's in Pakistan.

[vehicles beeping] [crowd chattering] - Okay, question.

- Uh huh?

- What did you think of her in real life?

- She's great.

- Yeah, but does he fancy her?

- Does he fancy her?

Zo, please don't say that on camera, come on.

So annoying.

- Fine.

- And are you nervous about the mehndi tonight?

- Actually, just tell me what that is.

- Well, in Pakistan we really like to draw out the wedding celebrations.

So, it's over three days.

With first is the mehndi, which is tonight.

And kinda like a stag and a hen rolled into one, except your grandparents are there, which is lovely.

And the groom isn't stripped naked and tied to a lamppost.

And then the next day is the Nikah, which that's the actual marriage.

And the Shaadi, then valima.

But the main thing is you have to look like you haven't enjoyed your first night together.

- What if you haven't enjoyed your first night together?

No comment?

- No comment.

[Christiane chuckles] - How much of it were you able to shoot in Pakistan and have you been able to show it in Pakistan?

Has there been an opening, - Yeah.

- a premier?

- So, it was COVID when we were shooting, so we couldn't actually travel there, but that's a second unit.

What you see there is the Pakistan scenes were shot... Actually, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, who I'm sure you've interviewed.

- Yes, great documentary.

- Fantastic documentary maker, and a good friend stepped in and oversaw the Pakistan shoot for us, and did all those scenes.

It was without the stars, we couldn't- - So, it was kinda CGI but real- - Yeah, it was a bit of magic of cinema.

- [Christiane] Wow.

- But those scenes are shot in Pakistan, but we just had to green screen the actors and we used body, we used doubles and we did all sorts, but yeah, so all the architecture and everything you see is Pakistan, and then extraordinarily, we managed to create a old haveli, a Pakistani style house, courtyard built round a courtyard in London.

And amazingly this incredible singer, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, who plays himself in the film and is the biggest, pretty much the biggest singer in South Asia, came and acted himself 'cause he happened to be in London at that moment, even though he's based in Pakistan.

[Rahat vocalizing] - You see?

He's gone mad.

- So, we had this wonderful scene and honestly, I defy Lahore's to watch it and tell me whether there's any, whether it was Lahore or London.

All of them have have said it's incredibly hard to tell the difference.

- So, I'm not gonna do a spoiler alert about who ends up with who, but what is next for Jemima Khan?

What's your next Hollywood or rather, film venture?

- Well, I've got some documentaries that are coming out this year, so I have a few things and I hope to write something again.

You'll probably see it in 2054.

- 2054 [laughs].

- That's how long it takes.

- No, you've got it down now.

It'll take less than 10 years.

Thank you so much.

- Thank you.

- Good luck.

The film is excellent.

It comes out here in the U.S. on May 5th.

Now, from rewriting cultural assumptions about love to the cutting edge science of new life, questions about having children took the writer Emily Witt to the limits of reproductive research.

In her latest piece for "The New Yorker," "The Future of Fertility," which reveals her discovery.

And she explains to Michel Martin how a few biotech startups could be about to change the game.

- Thanks, Christiane.

Emily Witt, thank you so much for talking with us today.

- It's great to be here.

- Before we get into your article, "The Future of Fertility," I wanted to ask about your book from 2016, "Future Sex."

Critically acclaimed, certainly made a lot of waves.

You explore sex and desire in the age of the internet.

Is there a through line between that work and this latest report on fertility?

- I think there really is because that book was about examining three major changes, one of which was people getting married much later or not at all, waiting longer to kind of settle down in the traditional sense, if they ever did.

And it was about changes in technology and also changes in our idea of what a family is and what a relationship is and a broader spectrum of identities and practices, and exploring all that.

And I think this does fit in because it's very tied to the new timeline that many of us live under.

And also, I don't know, new ideas of family, especially, I think.

- It's my understanding that it really kind of stemmed from your own personal questions about some of these issues.

What were some of those questions and do you still have them?

- Yeah, so I started writing that book when I turned 30 and this kind of, my parents have been married for more than 40 years and the relationship that they had and the traditional family that I grew up in just seemed very elusive to me.

And I wasn't sure if it was some kind of personal failing or some kind of structural change, but I noticed many other people around me in a similar situation and demographic changes that also reflected that many people were going through this at the same time.

And in the end I spent most of my 30s in relationships, but now I'm 42 and I'm single again.

And I think the book was in many ways about trying to figure out what was going on in my own life.

- So, in "The Future of Fertility," this is the piece that we wanna talk about that published in "The New Yorker," you profile new biotech startup firms working on producing reproductive cells, but without human ovaries.

Would you just tell us a little bit about the two companies that you focus on?

What exactly are they doing?

If you could explain this so that all of us can get it, and how does their research overlap?

- Yeah, so in the past 10 or 15 years, there's been major advancements in stem cell technology, which means that you can use a cell in your own body, the skin cell or a blood cell, turn that back into a cell that has the potential to become any other kind of cell in the body.

And that's been used to study cardiac problems, pancreatic problems, all kinds of things, but one kind of cell that they might make is an egg cell or a sperm cell that might help people with fertility issues.

So, I focused on two companies.

One is trying to make an egg cell from a stem cell, and the other one is trying to create basically the ovarian egg environment in which an egg cell matures so that an immature egg cell could be taken from the human body and then put in this environment which would kind of mimic the process of IVF, but hopefully be a little less invasive and time consuming.

- And there were major breakthroughs, I think before your piece was published.

Can you just tell us what they were and why they're important?

- Yeah, so they've achieved this in mice, but they haven't achieved it with humans yet.

And right before I went to press, one company, Conception, managed to bring the human excel to the follicular phase, which it's formed what's called a primary follicle, which means it's kind of ready to progress into a mature egg cell.

So that was a big advancement that shows the technology has a lot of promise.

And then similarly, this other company, Gamida, which is creating this kind of like lab made ovarian environment using lab made cells, had a similar breakthrough creating that environment and published a paper about that.

- Well, there's just so many dimensions to this.

There's the question of what this could potentially achieve for people.

So, let's just talk about that first.

Why is this something that that is appealing to people, not just the sort of scientists as kind of a thought exercise, "Can we do this?"

But how this has the potential to benefit humanity for want of a better way to put it?

So.

- Yeah, I think in a few ways.

I mean, first it would be really useful to couples suffering from infertility that wanna have a genetically related child, especially egg cells in particular are kind of scarce and they can be difficult to mature and grow and extract from the human body.

So that's one, just couples suffering from traditional fertility issues.

But one area that I was especially interested is in female reproductive longevity.

As we all know, women have a shorter reproductive lifespan than men do.

They're born with all the eggs they ever have and usually by the time they're in their early to mid forties, those eggs are no longer viable for reproduction.

And we live at a time when we're living longer, we start relationships later and that's caused a lot of, that's a big burden for a lot of women to try to fit their career, their relationships, their childbearing, all before the end of their thirties.

So, I think there's a real desire to prolong that timeline a little bit, which could have really massive repercussions.

And then the third demographic that this might affect are same-sex couples that would like to have a genetic child.

So Conception, the company that's working on making the human egg cell, was two of its co-founders are gay men.

And using that technology, it's possible that a cell taken from a male donor using this technology could be turned into an egg cell with two x chromosomes.

So, that's part of the promise too.

- So, let's talk about some of the concerns that have been raised about this, this kind of work.

Let's just start with the safety questions.

Are there any?

- Yeah, there's huge safety questions.

I mean, this is human life.

It's not even testing a pharmaceutical, it's human life.

So yeah, they would have to prove...

Assuming they accomplished this, which they haven't yet, they would first have to do animal studies across multiple generations to ensure that the genetic imprinting has happened kind of intact, that there's no inherited diseases that could only manifest a couple generations down the line.

And then there would need to be clinical trials of humans too.

And of course, like nobody would be confident about doing this unless it really felt safe as big as the desperation is on the part of people suffering from infertility.

- But then there's a broader sort of social concerns.

One is that, one of the things I was really glad that you raised in your piece is that the research into women's fertility overall or women's health overall, can we just say it?

Has not really been a priority of the scientific establishment ever, ever [laughs].

And so, one of the scientists whom you interviewed just said, "Hey, how about could we figure out like, just some of the things that affect women's health?

Could that be a higher priority?"

- Yeah, I mean, so, there's very little understanding of the causes of infertility beyond this biological timeline, but scientists don't even really understand, first of all, why menopause happens.

What triggers the timeline of it, when it starts, why there's such a large window.

It can happen to a woman in her mid thirties or it can happen to you when you're 50, and nobody really understands why or the effect of ovarian aging on aging in the rest of your body.

Nobody really, one thing I learned in this article that was really interesting to me is that humans are pretty unique among mammals in that their ovaries aged basically more than twice as fast as the other organs in the body, and including chimpanzees, our closest relative, they can reproduce almost to the end of their lives.

So, it's just this kind of black box that science doesn't quite understand, and the argument is that, yeah, if you could better understand that process, there might be a less kind of high intervention way of treating infertility, or at least prolonging reproductive longevity.

- And then there's the tension that you describe in your piece between, how these biotech startups share their information with the world versus kind of traditional academic scientific research.

Could you talk a little bit about that?

Because I think that kind of intersects with both the sort of core safety concerns and kind of the broader social concerns that others folks might wanna weigh in on.

Could you talk a little bit about that?

- Yeah, so this technology involves the creation of human embryos and there's limits on federal funding into that research, there's restrictions, and that means that the most of the money can come from the private sector or from states, but it means that biotech in the private sector has a major advantage in doing the research over traditional academic channels.

And I guess the worry is that the profit motive might perhaps obscure some of the basic science that needs to be done that an academic researcher working as at a slower pace might be able to achieve more thoroughly.

- How do you think that this also intersects with the intense debate going on right now about abortion access, primarily in the United States?

I mean, it's just, it really, and we're just such an interesting moment because you can't help but notice that in the United States there's kind of a major political push to restrict abortion access.

And so, how do you think this research intersects with this debate that we're having over access to abortion?

- Yeah, I mean, unfortunately in the United States, pretty much any research that has to do with pregnancy, embryos, fetal tissue is extremely polarized and politicized.

And that means that this technology likely, even if they're able to achieve it, one legal scholar told me that she expects that it would be more likely to be approved or tested in, for example, the UK before the U.S. because of our polarized political environment.

On the one hand you have a lot of people suffering from infertility that wanna have children.

On the other hand, you have these obstacles to scientific research that are rooted in a moral debate about conception and the beginning of life and all of that.

- Some of the researchers in your piece fear that this research, we'll call it IVG research for the sake of shorthand, and IVG stands for in vitro- - Gametogenesis.

- So- - Gametogenesis.

There are some who are concerned that this will mean a return to the idea that a genetic connection is essential for families.

What were some of the discussions that you encountered around that question?

- Yeah, certainly it raises the question of why is a genetic connection so important that you would go into such kind of extremes to achieve it?

And for some people that might seem self-explanatory.

For others, I don't know.

Is it worth it?

LGBTQ families in particular have fought for a couple of generations now for legal recognition of a social relationship with their child that's as meaningful and important and deserves as much legal recognition as a genetic one.

And yeah, so all of these questions will be coming up, I think if this becomes real.

- If and when IVG becomes available to the public, you have to assume it'll be very expensive.

I mean, in vitro is expensive.

So, is there a concern or did this come up in your reporting that this kind of further, I don't know, kind of widens the gap here between the haves and the have nots?

This is like yet another thing that we're, if you delay childbearing, then this becomes like the privilege of the few as opposed to something that human beings should be able to do.

- Yeah, that's absolutely a concern.

I mean, already assisted reproductive technology is not, there's not equal access to it.

It's often not covered by insurance.

And even if it is covered by insurance, it still can be very expensive.

So, this would almost certainly fall under that inequality.

And there's another question that's been brought up, which is that if you have a kind of unlimited supply of egg cells and could make more embryos, then it's also easier to do genetic selection on those embryos.

So, people might try to optimize for health outcomes for any number of factors, and it might result in a kind of divide where you have one part of the population that's kind of trying to create these extremely healthy children, and another part maybe that might not even be able to have access to contraception or terminate a pregnancy that's unwanted.

So, there's a lot of questions we'll have to ask about what this means, who has access.

Yeah, what it offers to the people that have access.

- And who gets to have a say in that?

What process is there by which the public gets to have its say about this, and express its values around this?

- Yeah, I mean it'll be...

I think we have a lot of historical precedents to go on, even contraception and access is so uneven, so limited.

People that want it can't get it.

It's sometimes covered by insurance and some places they don't wanna cover it.

It's an extremely polarized question.

And I can only imagine that this will be similarly polarized and that there will be kind of a feminist likely, I assume a sort of feminist articulation of what it would mean to have reproductive freedom in this context as well.

- And before we let you go, another universal question that affects all of us is climate.

There are those who argue that lower population does benefit the planet, who feel that overall this emphasis on increasing population, maintaining population is just the wrong direction to take given the state the status of the planet.

What are your thoughts about that?

- Yeah, I do have thoughts about that.

I mean, overall the population of the planet is still growing and is expected to grow, at least toward the latter end of the century.

But when you look at many countries, including the U.S., the fertility rate is a little bit below replacement rate, I think where a decline in people having children in their twenties has not been made up by an increase in people having children in their thirties.

I guess I would say that I don't think this is some kind of pronatalist push where you're pushing people to have more children than they wanna have.

I think who this really affects are people that are having trouble even having one child, and I think most of us can agree that having a child for people that want it, we should do everything possible for those people to be able to have a child and the population question, I don't...

The way that the world has been trending, the United States, many countries in the world now are people just don't wanna have a lot of kids.

So I don't think we really need to worry about how this would affect the kind of macro trend of population stabilization really.

- Hm.

- Emily Witt, thanks so much for talking with us today.

- Yeah, thank you.

- And that is it for our program tonight.

If you want to find out what's coming up on this show every night, sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thanks for watching Amanpour & Company, and join us again next week.

[inspirational music]

Support for PBS provided by: